The Ultimate Guide to Immersive Theatre: nearly everything you need to know

This ultimate guide covers the important aspects of immersive theatre for audience members and aspiring theatre-makers. Get curious in a deep dive with Fast Familiar.

If reading isn't your thing, you can listen to a recording of this post here...

(growled by Rachel in her best post-COVID voice)

What is immersive theatre?

Let’s lay the foundations for what we’re even talking about here.

What’s the history of immersive theatre in the UK?

Where did immersive theatre come from, and where is it going? What does it have to do with Virtual Reality and Escape Rooms?

So what will I have to do in an immersive theatre experience?

As an audience member in an immersive theatre show, this is what might be asked of you.

What if I do the wrong thing?

Spoiler alert: it’s not about you doing the wrong thing - it’s about the care that immersive theatre-makers should be taking of you.

Do I have to be good with technology?

How and why some immersive theatre companies are using digital technology. And no, you don’t have to be a whizkid, that’s on the makers too.

Why do people make immersive theatre?

Some stories ask to be told in one way - and others as immersive theatre.

I’d like to make immersive theatre too… what should I do?

We thought you’d never ask. Here are some starting points.

Immersive theatre is a small but perfectly formed part of the entertainment landscape of the UK. Some people can’t get enough of it. That feeling of being at the heart of the action, the intimacy of the immersive experience, the sense of (contained) risk. Other people might want to find out a bit more before they immerse themselves - and rightly so! What is it? What might you be asked to do? Is it like an escape room? Is it possible to get it wrong as an audience member? And how does it feel on the other side, for the immersive theatre-makers? This is your ultimate guide to immersive theatre.

Don't have time to read the whole guide right now?

Just pop your email in below and it’s yours to keep!

What is immersive theatre (and how is it different from other types of the theatre)?

Let’s begin at the beginning - what is immersive theatre anyway?

immersive theatre vs traditional theatre

There are all kinds of immersive theatre, but the thing that’s universally true of all immersive theatre is that the audience exist *within* the world of the story, rather than sitting outside watching it. In most other types of theatre, whether it’s Shakespeare, Hamilton or A Streetcar Named Desire, the audience watches what is happening from outside. They’re not inside Stella and Stanley’s apartment with them or serving in Macbeth’s army. They’re sat in an auditorium which looks… well, like an auditorium. Conversely, in immersive theatre, the audience is part of what is happening - they might be guests at Punchdrunk’s Masque of the Red Death or a parliamentary adviser to the 1979 Labour government, in Parabolic’s Crisis? What Crisis?

So what is this ‘immersion’ thing in an immersive experience?

The idea of immersion is pretty established in games studies. The games scholar Gordon Calleja distinguishes between different types of immersion:

- “immersion as absorption” is being totally absorbed by some activity or interest. You might lose track of time or forget about everything else going on in your life. Calleja uses the example of playing Tetris, which is highly absorbing but the player does not genuinely imagine they are watching bricks falling from the sky.

- “immersion as transportation” on the other hand, is where the player really does feel that they are in a different place to their real-world location: they are transported.

Some immersive theatre productions, for example, Fast Familiar’s The Evidence Chamber, are aiming for immersion as absorption; others, like ZU-UK’s Hotel Medea or Raucous’ Ice Road transport the audience through design and an all-encompassing atmosphere.

I’ve also heard words like ‘interactive theatre’, ‘playable theatre’, ‘audience-participation’… and audience-centric.

OK, let’s go for some definitions.

- immersive - you’re within the world of the story, rather than a spectator watching it. You don’t necessarily have any power to change what is happening around you. In Darkfield’s Ring, you are at a (terrifying) meeting - you absolutely feel you are there, but ‘all’ you are asked to do is to listen.

- interactive theatre - you as the audience are making choices that affect the rest of the experience. The show could not progress past the first choice point if there were no audience to make that choice. Some people (like Coney and UPSTART theatre) also use the term ‘playable’ for this type of experience; Coney's show A Small Town Anywhere is a great example.

- audience participation - I don’t know about you, but this makes me think of someone being called on stage during a pantomime or stand-up set - possibly feeling humiliated. This is the last thing most immersive theatre companies want, so you won’t hear this term very much.

- audience-centric - this is what Fast Familiar call our work because the audience is at the centre of what’s happening, and without them, the artwork is just a pile of iPads, an empty room or a web browser.

What’s the history of immersive theatre in the UK?

Search data from Google suggests that enough people cared about ‘immersive theatre’ by about 2008 to be searching it in large numbers. And searches have increased year on year since 2015 (until the COVID-19 pandemic hit). Of course, immersive theatre existed long before this - in her book Artificial Hells, Clare Bishop traces the roots of relational or participatory art - itself a cousin of immersive theatre - back to the 1910s. But immersive theatre in the UK, in the form it exists today, emerged in the 2000s.

Theatre gets immersive…

In 2006, immersive theatre superstars to-be Punchdrunk followed their first hit show, Faust, with Masque of the Red Death at Battersea Arts Centre in London. It played for a 7-month sold-out run - and more than 40,000 people went to see it. From 2008 to 2012, ZU-UK (then making work as Zecora Ura) had huge success with their overnight immersive trilogy Hotel Medea. Audiences witnessed the tragedy unfolding around them as night fell and then dawn broke. Experiences like this created audiences with an appetite for this type of performance - and other artists and companies were excited by its creative possibilities.

‘Immersive’ as a buzzword

As the currency of the word ‘immersive’ grew, it also became a way to market experiences and products that didn’t necessarily have much in common with immersive performance. In some quarters, there is a feeling that the term has become commercialised - or at least disconnected from its original meaning. In their Post-Immersive Manifesto, pioneers ZU-UK write: “Immersive theatre has become detached from its radical origins. Its appropriation by advertisers, events promoters and PR consultants has rendered it a shorthand for selling tickets to elaborate and expensive fancy dress parties…”

So what does this mean for the future of immersive performance? Some immersive theatre companies, like successful creators Swamp Motel, operate a business model incorporating luxury product launch events and more ‘artistic’ experiences. They use their skills to create for immersive across both events and experiences.

Immersive as XR

For many people, ‘immersive experiences’ have never been immersive theatre. For them, ‘immersive’ means experiences in VR (virtual reality), AR (augmented reality) and XR (mixed reality). These ‘immersive’ technologies are supported by various funding schemes keen to help them reach the ‘commercialisation’ stage - where they will be ready to make money and contribute to the economy. Some immersive theatre companies have tried their hand at immersive technology projects - but there haven’t been any breakthrough successes at the time of writing.

And what about escape rooms? Are they immersive too?

Escape rooms - games in which a team of players discover clues and solve puzzles to accomplish a specific goal - started growing in popularity around the same time as immersive theatre.

Some escape rooms employ actors, theatre designers and theatre writers. The best escape rooms are super immersive and interactive. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when face-to-face entertainment wasn’t possible, many escape rooms moved online - and a handful of immersive theatre companies (including Swamp Motel, Coney and Fast Familiar) also turned their hands to making digital puzzle games.

So what will I have to do?

Different immersive theatre shows invite their audiences to do different things. So let’s have a look at what might be on the menu…

‘Choose your own adventure’

When people think about stories where the audience have the power to make choices, they often think of ‘choose your own adventure’ or, as it’s otherwise known, branching narratives. In this format, audiences need to make regular choices that will affect what happens next in the story: explore the forest or check out the castle? There are overlaps here with interactive fiction, and some TV shows - notably Netflix’s 2018 interactive film Black Mirror: Bandersnatch - have also experimented with the format.

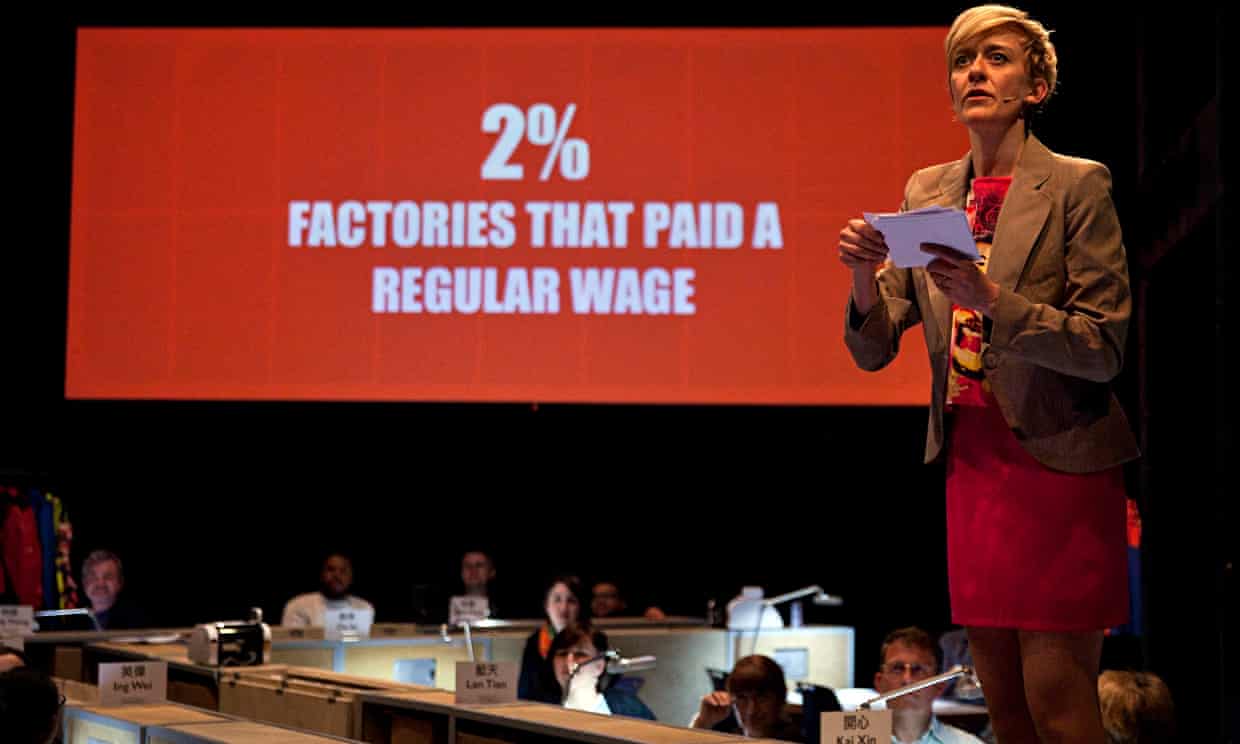

Within immersive theatre, Metis’ World Factory saw teams of six people ‘running’ a garment factory in China, making multiple decisions about what the factory should make, who it should employ and what conditions people should work under. But making branching narratives is time-consuming and expensive because you need to create hundreds or thousands of options - and your audience will only experience one of them. Some immersive theatre companies aren’t keen on branching narratives because they involve giving a lot of control away to the audience - who might well make decisions that deliver a dull evening.

So what other types of choices might I be making?

Some immersive theatre experiences are arranged around a singular choice. In Fast Familiar’s week-long thriller Smoking Gun, a group of anonymous strangers receive information from a whistleblower. The experience asks them to piece the information together and decide whether to go to the press: they know from the start that they will need to make this choice. Other immersive theatre shows, like Jamal Harewood’s The Privileged, explore the audience’s boundaries around what they’ll tolerate - and what’s needed for them to be forced to act.

Will I always be making choices?

No. Well yes and no. Sometimes the choice will be where to go. In shows like The Drowned Man by immersive theatre superstars Punchdrunk, audiences navigate their own routes through a building, free to explore at will. There aren’t choices that will impact the story, but the way you choose will determine the bits of the action that you see - or don’t see.

What if I do the wrong thing?

It’s totally normal to be worried about this - but if the immersive theatre company is any good, they will have thought very carefully about how to support you as you experience their work.

Theatre-makers have a duty of care

Lots of immersive theatre asks audiences to take more risks than they would in traditional theatre - making choices or moving around or something else that can leave people feeling exposed or vulnerable. If they are working with integrity, theatre-makers will be very conscious of this and reward their audience proportionately for taking these risks.

Fast Familiar talk about inviting people into immersive theatre as an act of hospitality; the word ‘hospitality’ originally meant the power that the host has over the stranger/ enemy. In the act of hospitality, you have enormous power over the strangers you are welcoming - and a responsibility to use that power for good, not evil. Extending this hospitality and accepting a level of responsibility for audiences’ emotional well-being doesn’t have to mean that all immersive experiences have to be cutesy and anodyne. Indeed, some aren’t.

Don’t worry if there are tricky bits

Different immersive theatre companies will have different tastes, which will affect what they ask from audiences. Individual audience members will have different appetites for risk. If you hit a challenging patch in an immersive show, don’t assume that it’s because you’ve made an error. Indeed, it might be part of the design. The play scholar Miguel Sicart suggests that play doesn’t have to be fun, but it does have to be pleasurable.

An immersive experience doesn’t have to be lovely all the time: solving a tough puzzle can be as satisfying as something light and fluffy all the way through. Some immersive theatre-makers aim to take audiences to a tough place and bring them back safely because they feel that is likely to be more satisfying than keeping the whole experience above the discomfort line.

Do I have to be good with technology?

The short answer here is ‘no’: the responsibility for the tech being usable and intuitive, rather than presenting a barrier to audiences, is 100% on the theatre-makers.

Immersive theatre and the COVID-19 pandemic

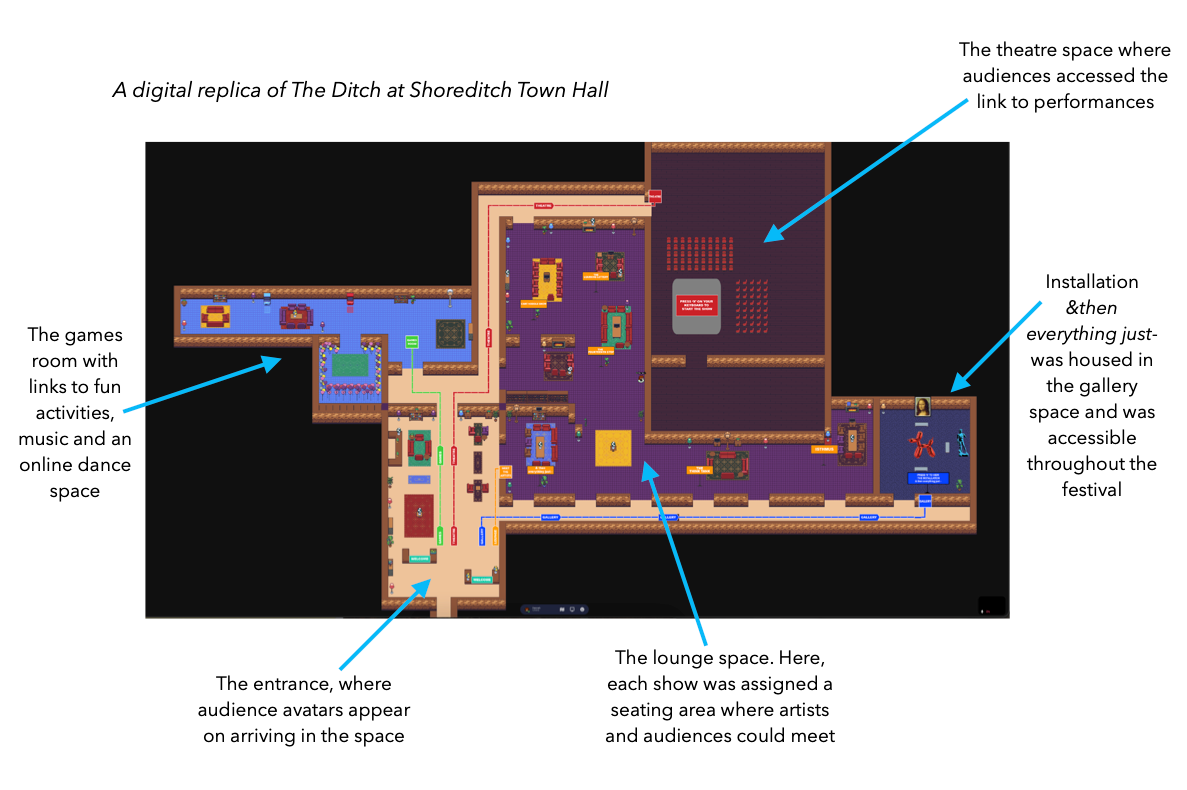

The majority of immersive theatre relies on actors or other facilitators to interface with an audience: some immersive theatre doesn’t involve any technology at all. Other pieces might ask you to use your phone or some other piece of tech. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many theatre-makers experimented with digital technology to keep working when it wasn’t possible to congregate in physical space. For many immersive theatre companies, this opened up new possibilities. Artists often repurposed existing apps and platforms. German company machina eX used the messaging platform Telegram for their show Homecoming, and UPSTART Theatre ran their annual festival of playable theatre, DARE, in gather.

So why would anyone risk using tech in immersive theatre when there isn’t a pandemic?

Everyone knows that technology breaks, runs out of batteries and is - sometimes - secretly trying to ruin our lives. So why would anyone choose to introduce technology in an immersive theatre context, where there are already so many chaos variables?

If you’ve been to a handful of immersive theatre shows, you’ll probably have experienced moments where you’re frightened of embarrassment. Either embarrassing yourself by doing the ‘wrong’ thing or embarrassing the performers by doing something that they weren’t anticipating - something they don’t have an answer to. The theatre scholar Gareth White has written extensively about this fear of embarrassment. He notes that “when participatory performance invites performances from audience members, it presents special opportunities for embarrassment.” Indeed it does. He also draws on the Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman’s observation that people engage in ‘defensive practices’ to save themselves from embarrassment - but we also use ‘protective practices’ or ‘tact’ to protect other people from being embarrassed. These protective practices can inhibit people in an immersive theatre setting.

Fast Familiar, who combine theatre and computing expertise, use tablet devices to mediate their immersive face-to-face courtroom experience The Justice Syndicate because you can’t embarrass or offend an iPad. Players use their iPad to access evidence and anonymously register their vote on whether the accused is guilty or not guilty. This mechanism also allows participants to know how the group is leaning without experiencing public embarrassment if their vote isn’t in line with that.

Why do people make immersive theatre?

You’ll have heard the showbiz advice, ‘never work with children or animals.’ Making immersive theatre can feel like taking a nursery school class on a visit to a safari park. So why on earth does anyone make it?

Form follows theme

The idea of confining an audience to sit still in the dark, with a singular expression of how they feel (clapping at the end), just doesn’t feel appropriate for some immersive theatre-makers. This isn’t a criticism of the traditional audience setup. It’s more that something about the theme or subject matter of the artwork asks for a different set of behaviours from an audience.

For example, Fast Familiar started making interactive theatre because they felt a tension between the climate activist themes of their work and a form that required audiences to sit passively. TalkShow Theatre’s first show Ten out of Ten explored ideas of success and failure and positioned audiences on isolated chairs in rows to evoke the high-stakes emotions of taking an exam. The subject matter of the artwork drove these choices.

Different every night

Not knowing how the show will end is exciting or terrifying, depending on how you look at it.

It’s not for everyone, but a great many immersive theatre-makers would admit that for them, an artwork that plays out the same every time is limited in its interestingness. In some ways, immersive theatre is the performance equivalent of extreme sports.

It can also be fascinating to watch a group of people collectively address a problem. So much media coverage can lead you to believe that humans are horrible, selfish and incapable of collaborating. Experiences in immersive theatre productions can show the opposite: people’s resourcefulness and capacity for generosity.

That sounds amazing - I’d like to make immersive theatre too… what should I do?

Excellent, a convert! Welcome to the wonderful world of immersive, your next task is to…

Experience as much as you can

If you’re reading this, you’re probably already doing this. Try to expose yourself to as much immersive and interactive theatre as possible - all of the companies named in this piece are well worth checking out. And there are many others.

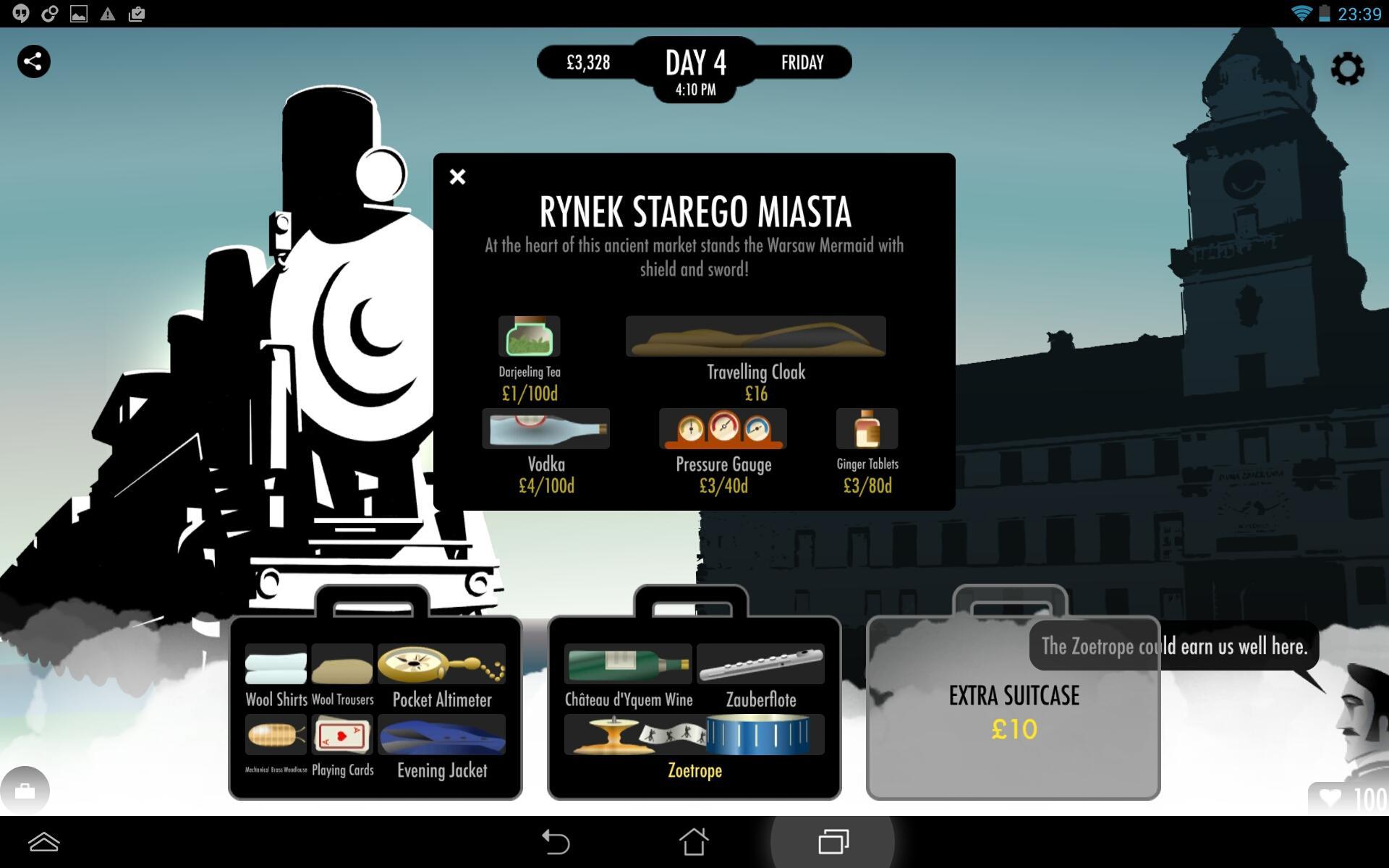

Also, play some games - theatre people can sometimes be a bit sniffy about computer games, but immersive theatre has a lot to learn from them. Inkle’s 80 Days is a masterpiece in how to write a re-playable branching narrative; Robert Yang’s work explores queer identities and representation in a way that is streets ahead of most immersive theatre; and Die Gute Fabrik (whose CEO is an ex-theatre person) won tons of acclaim for their game Mutazione.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a rise in online puzzle games and escape rooms - those by immersive theatre companies like Swamp Motel and Fast Familiar tend to be narratively driven, so are well worth checking out. Lots of companies need to give their projects a trial run or 'playtest' them before releasing them to a general audience, so if you sign up to their mailing lists, there are often opportunities to experience their work for free. By ‘immersing yourself’ (arf arf) in what already exists, you’ll learn about your tastes and the unique things you could bring.

Watch people

Not in a creepy way, but notice what people do. At a basic level, if you create work where the audience makes choices or somehow determines an element of what might happen, you are dealing with why people do stuff. So you’ll benefit from basic awareness of human psychology and neuroscience. Read some books on it or find someone who knows about it and invite them into your process.

Just make something

Immersive theatre is a relatively young art form, and let’s be honest, a lot of the stuff out there is very bad. No one has made the definitive piece of immersive theatre yet. So if you’re genuinely interested in immersive experiences, collaborating with an audience, and you’re committed to working with care and integrity - please, get out there and make your immersive theatre show.