The power to choose: adventures with interactive audiences

In traditional theatre, the audience’s main job is to watch. But when you’re making experiences for interactive audiences, there’s a whole lot more to consider.

What’s the role of a theatre audience?

You can listen to Rachel reading the full post here...

In traditional theatre, the audience’s main job is to watch - and feel and imagine. Sometimes makers of interactive experiences can annoy more traditional theatre people by calling this ‘passive’ and what they, the interactive people, make as ‘active’ for an audience. This isn’t particularly helpful, as even when sat in a traditional auditorium in the dark, some watching requires lots of concentration and lots of imagination.

In Elevator Repair Service’s Gatz, the actor Scott Shepherd comes onto a stage designed like an office, takes a copy of The Great Gatsby from a drawer and starts to read it. The production -all six hours of it- is every word from the book read by Shepherd and other cast members. Everything plays out in the office onstage but somehow, all the different locations of the book are conjured through a mixture of extraordinary theatre craft and audience imagination. The audiences are spectators yes, but passive, no. For the record, it’s one of the best pieces of theatre I have ever experienced. But there is a difference between what is being asked of an audience in Gatz to what’s being asked of them in Immersive Everywhere’s successful Immersive Gatsby, another theatrical rendering of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel.

No time to finish reading this now, or want it as a document to keep?

Pop your email in below and it's yours!

So what is the role of an interactive audience?

Like with all good questions, the answer is ‘it depends’. In audience-centred performance, the basic idea is that audiences have some degree of agency - that is to say, they have some control over what their experience is. Watching the brilliant Gatz, I can choose where on the stage to look, I can close my eyes, I can cover my ears. I could take mind-altering substances before I watch, which would affect my experience (I didn’t). But that’s the level of agency I have. I am not welcome to walk around, interact with other audience members or actors, and I certainly can’t change how the story ends. (T. J. Eckleberg will always be watching you). Depending on my role as an interactive audience member, I may be able to do all these things - in fact, the show might not be able to continue without me doing them.

Is the power to choose always Good?

Another unhelpful binary that can emerge right about now is: lots of audience agency = good/ no audience agency = bad. Audience agency isn’t de facto a Good Thing. Whether audiences have a good time or not is going to depend on how their agency plays out within the show. Netflix’s 2018 interactive film Black Mirror: Bandersnatch was widely praised for its technical design but there was a more mixed reception to the narrative and the extent to which viewer choices affected the story. There were a lot of choices. A friend commented to me that they really didn’t care what breakfast cereal the protagonist ate, unless this was going to have consequences down the line (it didn’t). To many people, it felt like ‘choices for choices’ sake’, raising the question does agency really have any value when it’s over something inconsequential?

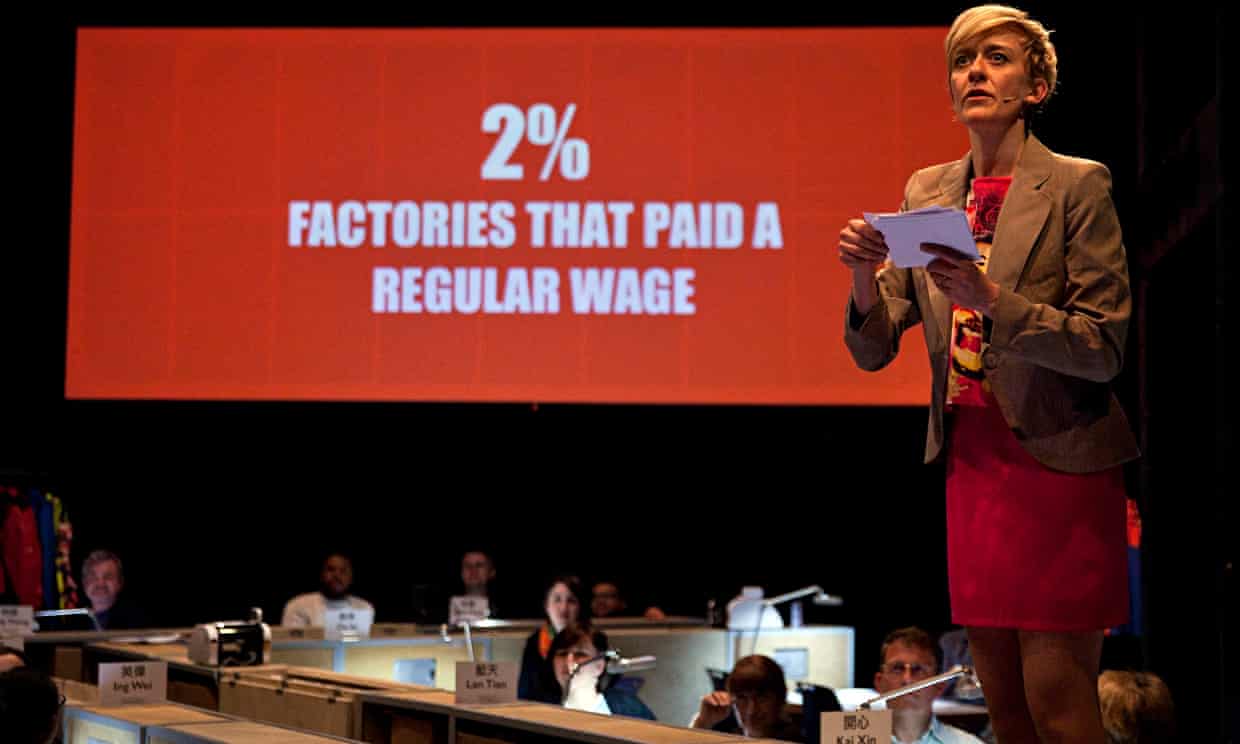

But the ‘choose your own adventure’ or ‘branching narrative’ format is what many people think of when the idea of interactive or immersive theatre is suggested to them. And there are some good examples of this. Metis’ World Factory saw teams of six people ‘running’ a garment factory in China, making multiple decisions about what the factory should make, who it should employ and what conditions they should work under. Early Days of a Better Nation by Coney is a less decision-dense scenario game where the audience is divided into three territories who make decisions about how their newly-formed country should be governed. In both these pieces, audiences had agency over how the story played out. (My factory went bust and my territory emerged as the dominant power in the new nation.) Making ‘choose your own’ adventure format interactive experiences means that you as the creator will make much more material than any audience member will encounter. If there were a trillion different pathways through Bandersnatch, there can’t have been many fewer through World Factory. This has budgetary implications - and also raises dramaturgical questions.

Immersive theatre and games company Blast Theory openly state that they don’t make branching narratives. For Fast Familiar, it’s not a format we regularly use either. For us, it’s about the dramaturgy of the experience - the overall journey that audiences go on. An audience member midway through the show isn’t necessarily going to make a decision that will deliver the most exciting end later, or that will pay off a decision they took earlier. It might be exciting in the moment to make a decision but there’s a risk that you then sacrifice the wider experience.

Even making the ‘right’ decision for that particular moment might not deliver the most interesting story - think of all the films which see the protagonist hit absolute rock-bottom before achieving a recovery that is therefore all the sweeter. High audience agency in the ‘choose your own adventure’ format doesn’t necessarily deliver a good experience for the interactive audience member.

Although, having said that, we’ve played Inkle’s interactive fiction ‘choose your own adventure’ game 80 Days through three times now, and had a brilliant experience each time. So maybe we’re just not clever enough to build dramaturgical structures which will withstand any sequence of audience decisions!

A menu of interactive audience agency

When we’re thinking about audience-centred theatre, we think about it in terms of what element we’re collaborating with an audiences on - or which bit of agency we’re giving to the audience. For us, that’s a more helpful way of thinking about audience agency than it being an amount (and what units would you measure interactive audience agency in anyway?). We break the different elements down as:

agency over what happens (in a story world)

This is the classic ‘choose your own adventure’/ branching narrative - like World Factory, Bandersnatch or 80 Days.

agency over what happens (in real word)

This exists more within the art and gallery-based practice world than immersive theatre, because of the real-world element - a good example would be Marina Abramović’s The Artist is Present. It’s also true of some alternate reality games (ARGs) like I Love Bees.

agency over how it happens

This is where most of Fast Familiar’s work sits. In The Justice Syndicate, the audience are a jury. They review evidence that is presented to them (this happens the same in every show). But what evidence they choose to focus on, what they discuss and ultimately the verdict they reach (guilty or not guilty) is down to them. All audiences follow the same steps but shows can differ enormously depending on how this happens.

agency over why it happens

I don’t have a good example for this. It would probably sit within the live art world and would involve audience members making sense of a seemingly unrelated series of events. There’s probably an argument that this doesn’t count as agency but we’ll leave that for another time.

agency over who does what in the happening

This is only possible in an experience for a group. In 2017, Fast Familiar made a show called Disaster Party which we don’t do anymore. That show ended with 7 characters surviving but it was up to each audience to decide who that would be, as well as who did what in the events leading up to this final decision.

agency over where it happens

This is about where an audience member’s experience takes place. In the shows of immersive theatre megastars Punchdrunk, audiences are allowed/ encouraged to roam around a series of rooms. (This has a ‘choose your own adventure’ element to it, as you may miss all the exciting things taking place because you happen to be in another room at the time.) The element of exploration is central to their take on immersion. In a very different take on agency over where the audience’s experience happens, for Fast Familiar’s immersive audio walk A Walk in the Park, participants are invited to do the walk in a park or recreation space close to where they live, opening the experience to an element of serendipity as local events may complement the audio aspect.

To be very clear, none of these types of audience agency are ‘better’ or more valuable than others - it’s a matter of personal taste, for both interactive audiences and makers.

What does agency look like? How can you tell if someone is ‘doing agency’?

Psychologists talk about three aspects of agency, which theatre scholar Astrid Breel has adapted in her study of agency in interactive and immersive theatre. These are:

- The intentional aspect (this is defined as a “perceptual sense that my action is having an effect”)

- The bodily sensation (feeling through my body that I did something and receiving feedback through my senses that what I did had some effect on the world)

- The reflective attribution (this is where I reflect on the experience afterwards and think that I had agency - or that I didn’t).

The difference between 1 and 2, which happen in the moment and 3, which happens afterwards, lead to an interesting effect which Astrid Breel has studied. To an observer, someone might seem to be exhibiting lots of “agentive behaviour” but when they reflect on the experience afterwards, they don’t feel that they had an “experience of agency.”

This is something that we have observed with audiences in The Justice Syndicate. Audience members vote and talk, engaging in “agentive behaviours” not associated with traditional theatre. However, when we ask audience members after the performance whether they experienced a sense of agency, some will say that they did and some that they didn’t. Often the people who didn’t feel agency are the people whose viewpoint was ‘defeated’ - where the votes of the group went against their opinion of whether the defendant was guilty or not guilty and the arguments they made in support of this position. They feel like they didn’t have agency because they didn’t succeed in changing the way that people voted.

Astrid Breel also argues that it is misguided of theatre makers to talk about “giving” agency to audience members. People already have agency; they have it when they walk into the show and it is not something theatre makers can give them. She talks instead about “conducting agency” - as theatre makers can guide the agency of audience members in certain directions. So the word ‘agency’, which often gets bandied around in discussion of interactive and immersive performance, is a lot more complex than it seems at a first glance. If there was a fine for using the word ‘agency’ to mean ‘people walking around’, it wouldn’t be long before you collected the budget for a small immersive show.

What even is audience-centred theatre? Or an interactive audience? Let’s attempt some definitions...

Is there any difference between the words that get used to describe kinds of work where we’re sharing agency with an interactive audience? I think yes, so here we go…

Immersive

Experiences where you’re within the world of the story, rather than a spectator watching it. You don’t necessarily affect what happens but it is happening all around you. All of Punchdrunk’s work would sit in this category - lusciously-designed environments and the anonymisation of other audience members hidden behind their masks make you feel like you’re somewhere else. I haven’t seen Immersive Gatsby but I would assume that too fits in this category. Fast Familiar’s The Window, a binaural experience to be listened to in the dark, and situating you within the story but not asking for any action in response, would also be immersive (in my book). As would binaural experiences by people like Darkfield. And theatre shows by Raucous.

Not all immersive experiences can be counted as audience-centred, i.e. can only take place with the participation of an audience… presumably Punchdrunk don’t actually need their masked audience members to do anything apart from spectate?

(Also, in the last 5 years, immersive has also started to be used for experiences that use ‘immersive technology’ - so virtual or augmented reality (VR/ AR). Confusing, huh?)

Audience-centred/ interactive

Experiences which can’t happen without an audience - they’d get stuck at the first choice point if there was no audience to make the choice. Work by Coney, Swamp Motel, Metis, and Fast Familiar would sit in this category. Our show The Justice Syndicate is twelve iPads on a table where there’s no audience - it isn’t a piece of theatre.

Audience participation

This makes me think of someone being called onstage during a pantomime or stand-up set, and very possibly being humiliated. BUT this is what lots of people think of/ assume when you talk about interactive performance, so I make sure I explain that this is not what Fast Familiar do. For us, the audience aren’t participating in the show, they are the show, and no one who isn’t also participating is watching them.

Relational art

<new term incoming> The French curator Nicolas Bourriaud published a book called Relational Aesthetics in 1998 in which he defined the term as: “A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space”. So relational artworks create a social environment in which people come together to participate in a shared activity. Is there overlap with audience-centred artwork? Yes, but because this is from the art-world rather than the theatre-world, story or narrative is generally less of a thing.

At the end of the day, probably the amount of people who would lose sleep over these definitions is significantly smaller than the amount of people who’d attend a Punchdrunk show for one performance. But it is important - the specificity we exercise while creating this kind of work will help us make nuanced and transformative experiences for the people who do matter: the audiences.