The Strategy Room 1/3: creating a design brief

From May 2022 to March 2023, Fast Familiar’s main focus was a climate action public engagement project called The Strategy Room. This blog documents the principles underlying the experience we created.

Introduction

From May 2022 to March 2023, Fast Familiar’s main focus was a climate action public engagement project called The Strategy Room. This blog documents our learning, in the hopes that it might be useful to other people working in climate or creative approaches to public engagement and policy development.

There will be official research outputs from the project produced by our partners Nesta: I’ll link to these once they exist. This is a totally subjective account, written by Rachel (who led on the project). FF try to share our processes, learnings and mistakes (to avoid other people needing to repeat them) and this documentation is part of that commitment.

The documentation of The Strategy Room is in three chapters:

- the process of creating a design brief - this is likely to be interesting for people who work through co-creation, people making public engagement projects and generally people working in climate engagement

- the structure of the project and its delivery - for people who make audience-centric and interactive experiences - and people working with local authorities

- the 5 things we learned - read this if you work in climate engagement - or actually any area trying to engage a broad range of people (with a complex subject)

Each of the three chapters is a standalone piece; if you’re going to read all of them, it would make most sense to read them in this order. This is Chapter 1.

The Strategy Room was commissioned by the Centre for Collective Intelligence Design (CCID) at Nesta. They published a tender which FF applied for, in collaboration with UCL’s Climate Action Unit (CAU), which is headed up by our longtime collaborator and friend Kris De Meyer. The brief was to make a participatory experience which would help local authorities understand what net zero measures could have support in their area.

You can listen to Rachel reading the full post here…

Chapter 1: the process of creating a design brief

During the process of putting together the tender application, we arrived at a series of principles which formed a kind of design brief. We added to this in the first few months of the project, as we orientated within the subject matter and the delivery context. This design brief is the hidden skeleton for the experience we ended up creating; a set of principles that supported everything else. Without this skeleton, the experience wouldn’t have stood up.

1. The experience should be co-created with users

To some extent, this is true of everything that FF makes, but our principle is always that the further away from our experiences the end users are, the more present they need to be in the process. No one at FF had experience of working in local authorities, although Kris had worked lots with them. Due to the projects we make, we probably spend more time thinking about climate change than the average UK citizen. So we needed to centre the experiences of local authorities and of people who didn’t spend half their lives thinking about climate action.

This manifested in working closely with three local authorities (Lambeth, Sandwell and Southend) to co-create the project, in a process that looked like this:

- June 2022: initial workshops with council officers and residents

- August 2022: check-in with council officers (from a wider group of LAs than our co-creation partners) about the policy content

- October 2022: extensive testing of a paper version of the experience with residents in our co-creation local authorities

- December 2022: UX testing with council officers and the residents of one local authority

- January - March 2023: delivery (more info here)

2. The experience should work for someone with no prior knowledge of climate change

This project needed to reach beyond ‘the climate choir’. i.e. beyond those people whose voices are already very present in debates around climate action (and who tend to be relatively affluent and mostly white). As we know from past work and have documented elsewhere, the biggest obstacle to interactivity is fear - and one of the best ways to activate fear is to make people feel stupid, or like they’re ‘the wrong people’ to be participating. Our worst nightmare was someone going away from The Strategy Room feeling like they weren’t entitled to an opinion or that they were superfluous to the action that needs to be taken on climate. So we decided that the most equitable thing to do was to assume no prior knowledge of climate change.

This meant having explainer animations for each ‘module’ of the experience. It also meant initially explaining all the terms we used - and then seeing what terms we could do without, because all that explanation was becoming a barrier in itself. For example, we decided not to use the term ‘net zero’ anywhere in the experience - testing with residents showed that it was really hard to explain, had negative associations (who really thinks that Coke Zero is nicer than regular Coke?!), and that we actually didn’t need it.

3. The experience should last an hour

People are busy. They don’t have time in their lives for everything that needs to be done, let alone some extra meeting - especially if climate action isn’t high on their list of priorities. We knew that we’d pay participants for their time but still, you have to respect the other pressures people have in their lives. We bent this principle a little by making an experience that was modular - so there’s 75 minute versions and 120 minute versions of The Strategy Room. We failed to make a 60 minute version - it just wasn’t possible to do this while explaining everything properly. Sometimes you have design principles which can’t be resolved against each other.

4. The experience should avoid a ‘will they/ won’t they save the world’ structure

Lots of games and interactive experiences about climate change have the participants making a series of decisions which result either in saving the world (winning), or failing to save the world (not winning). It’s a compelling game mechanic and there are lots of great games which use it, many of which we played as research. It’s also something that I find problematic on a whole bunch of levels.

- Maybe I don’t have a sense of humour but I kind of think this mechanism is too important to be your game driver. I know there have always been ‘save the world’ type games but it just feels a little close to be comfortable. To me, it feels especially grim when you consider the people and places that are already being affected horrendously by the effects of climate change - predominantly Global South countries and peoples. I just wonder if it’s a feature of Global North white privilege that those things are just penalty cards on a board for people like me - when they’re other people’s lived experience. Maybe this is me being ‘woke’ but it gives me the ick and when you work this hard on a project for the best part of the year, you don’t want it giving you the ick.

- Any ‘will they/ won’t they’ game needs a scoring system and that often takes a long time to explain and requires a decent chunk of gameplay to become meaningful. This doesn’t fit well with trying to make an hour-long game. It can also get into maths territory, which isn’t everyone’s favourite place to be - and can activate feelings of ‘I’m not smart enough’ or ‘I’m not the right person’ - which we always want to avoid.

- We need more positive visions of the future. We really don’t need any more dystopias or disaster scenarios - existing films, TV shows and books have those covered. We need to help people imagine what a positive future could be like, because, put simply, until we can imagine it, we can’t make it happen. That’s the common sense explanation; Kris has also written extensively, from a scientific point of view, about why we need positive visions. So we knew we didn’t want an experience which had a chance of ending in the world not getting saved.

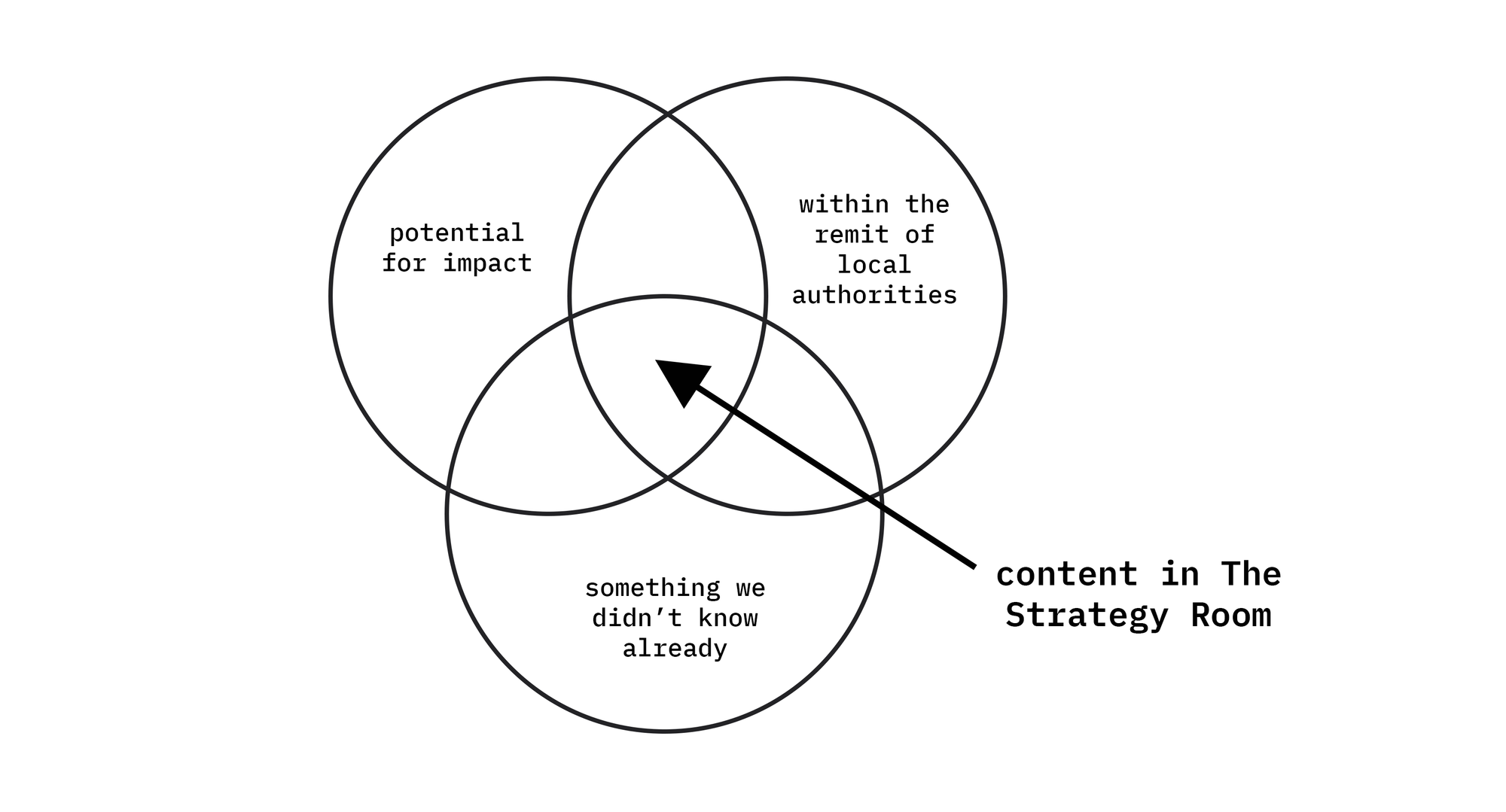

5. Content should fulfil our Venn diagram criteria

In terms of the content of the experience (the ideas or policies that participants would be presented with) we had three criteria for selection:

- impact - the ideas in the experience needed to have the potential for generating significant reductions in emissions. There are all sorts of types of climate action which are good and feel nice to do, but when you crunch the numbers, they’re just not that impactful. We decided to include only those measures with the potential for significant carbon reduction.

- within the remit of local authorities - this project was about working with local authorities so we needed to be presenting participants with policies that local authorities would have the power to implement. This criteria required the most back and forth with our co-creation local authorities, and was the hardest to stick to - for example, many transport policies would need to be London-wide rather than happen just in Lambeth or Wandsworth; lots of local action on domestic heating would need to be supported by initiatives from central government. The ideas in the food module sit at national rather than local level, although the experience is shaped to explore how local action could support implementation.

- something we didn’t know already - whenever we start a new project, I ask the commissioner to describe their worst version of the project - what would happen if we took every wrong decision from now on? When I asked Kathy from CCID this question, one of her answers was ‘it doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t know already.’ Indeed - what’s the point of spending a load of time and money proving some things that a reasonably clued-up person could have predicted? Fulfilling this criteria meant doing a lot of reading up on existing surveys and experiments, and finding out about some new approaches and policies that the public haven’t had the chance to express their opinions on yet. It also affected how we framed some of the ideas, which you can read more about here.

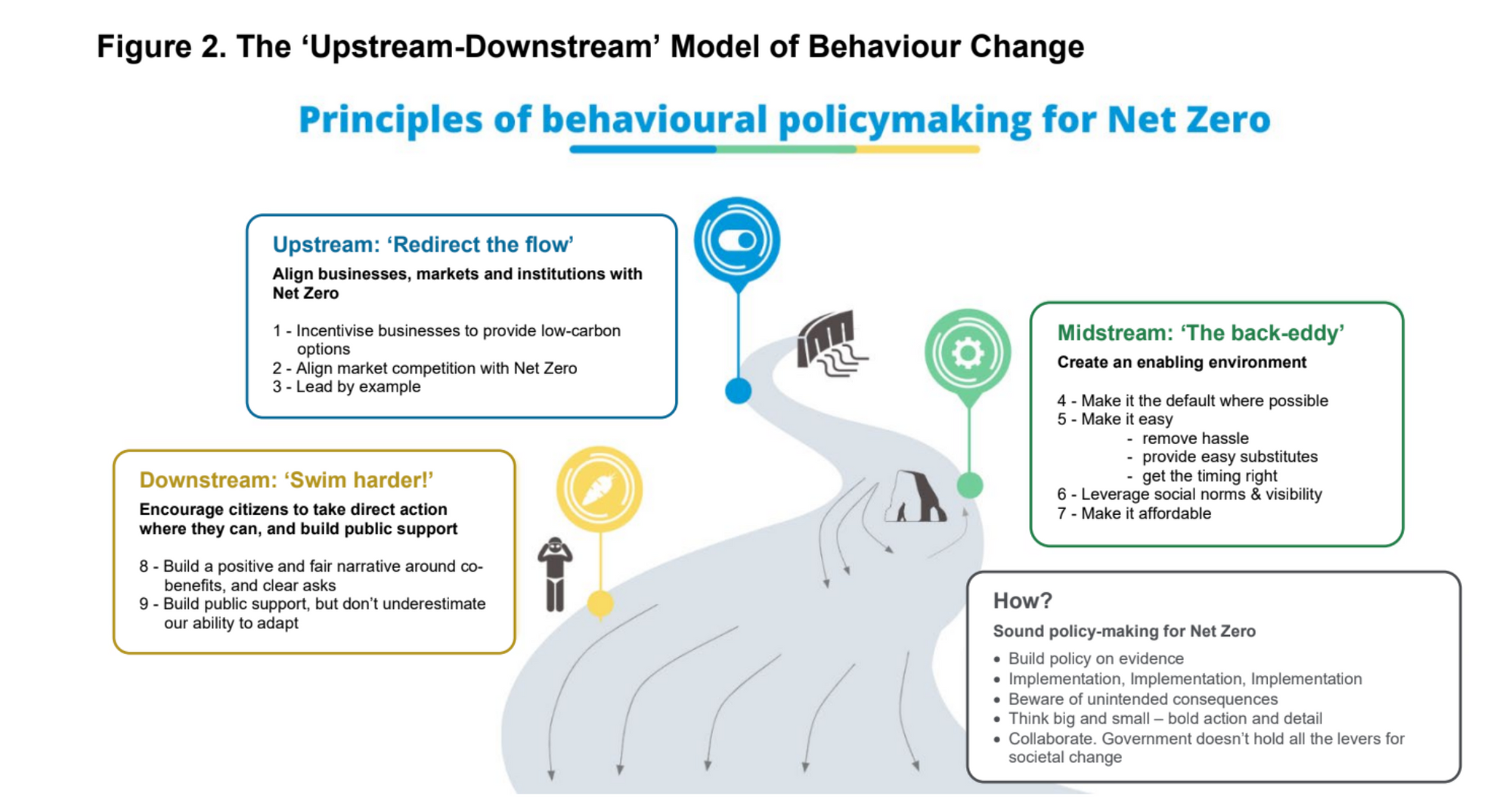

6. The experience should be about mid and upstream structural change, not downstream or individual change

For a long time, climate change communication in the UK has focused on the individual - telling people to switch lights off, recycle, travel by bike instead of taking the car. However, in recent years, some former proponents of this approach and the theory of ‘nudge’ that accompanied it, have begun to criticise it for the fact it doesn’t really work and that it could potentially do more harm than good. They have suggested taking an approach more focused on the structures or context that people are operating in.

To take the bike example, if you want more people to cycle, you could tell them that it’s better for the environment and their health. You could tell them that over and over again but if the roads are dangerous for cyclists, there isn’t anywhere for people to lock their bikes, and there’s a high level of bike theft, people are unlikely to swap their car for a bike. However, if you change the context, by creating cycle lanes separate from the road, making popular routes faster to cycle than drive, and provide affordable rental bikes for people who don’t want to or can’t own one, you’re likely to see an increase in cycling. This example illustrates the difference between downstream change, where you’re essentially shouting at people to swim harder against the current, and midstream or upstream change, where you’re making a change to the context - how the river flows - which makes it easier for people to make the ‘right’ choice.

Our focus on mid- or upstream interventions plays into the Venn diagram criteria number 3 - because climate change communication has for so long been focused on ‘education’, there are a whole load of structural changes where we just don’t know what the public think. These changes are likely to be more expensive than sticking a leaflet through people’s doors - but also more impactful because of the potential scale of change - it’s not a case of convincing each individual to make the changes themselves.

7. It wasn’t that easy

With hindsight, it’s easy to narrativise what happened into a neat and orderly account. The above hugely underplays the amount of work that went into this project, trying essentially to get to degree-level expertise on town planning, ethical investment, and various types of carbon tax (carbon tax didn’t end up in the experience but I can now talk about it at length if required… you’re spared right now).

We spent a particularly memorable/ miserable week in York in August 2022 teaching a Teenage Digital Art School for Mediale by day - and then by night and by painfully early morning, trawling through huge numbers of research papers. We’re enormously grateful to everyone who answered our emails, made introductions for us, and agreed to let us interview them. And to Kris who dealt with calls where we just expressed disbelief that we could ever wrestle all this information down into any sort of experience for the public.

The project was also challenging because of the need to keep up with the evolving situation: for example, a policy which was part of the heat module was swopped out at the last minute because political developments at national level made it highly unlikely that local government would ever be able to implement it. We also made this project during the steepest rise in the cost of living since the 1970s; this, and continuing Russian aggression against Ukraine made policies like community energy generation salient in a way that they probably wouldn’t have been twelve months previously.