What is immersion? Beyond the buzzword…

Here we draw on perspectives from games and psychology to ask ‘what is immersion, and how do we achieve it?’

You can listen to Rachel reading the full post here…

Immersive theatre, immersive experiences, immersive exhibits. Other than jumping in a swimming pool, what is immersion and why does it matter? Hold onto your hats while we go on a whistlestop immersive* tour of what’s going on with this word, and the connection between flow and theatre.

*It won’t be immersive but people seem to use ‘immersive’ now to mean ‘cool’ or ‘exciting’ so excuse me for temporarily jumping on that bandwagon. I’ve got off the bandwagon now. Sorry. Let’s go.

Too busy to get immersed right now, or want this as a document to keep?

Pop your email in below and it’s yours!

So what is immersion from a games perspective?

The games scholar Gordon Calleja distinguishes between different types of immersion in games studies, and drama scholar Josephine Machon has adapted these to a theatrical context in her book Immersive Theatres. Calleja describes “immersion as absorption” as being “absorption in some condition, action, interest.” He uses the example of playing Tetris, which is highly absorbing but the player does not genuinely imagine they are watching bricks falling from the sky. In “immersion as transportation”, however, the player does feel that they are transported to a different place from where they really are - for example in the video game, Half-Life 2 which, Calleja says, “presents the player not just with an engaging activity, but also with a world to be navigated.”

Using these terms, you could say that Fast Familiar’s The Justice Syndicate creates “immersion as absorption” (reviewers have talked about being “totally immersed in the experience”) but it doesn’t create “immersion as transportation” - and doesn’t try to. A piece like Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, for example, does create “immersion as transportation”, transporting its audience from a warehouse in London to a hotel in the 1930s, through the use of lavish sets and costumes that completely surround the audience member.

Josephine Machon adds a third concept, which she calls “total immersion” which combines “immersion as absorption” and “immersion as transportation.” I don’t think that I’ve ever experienced a piece of theatre that achieves this “total immersion” but maybe I’ve just been unlucky.

So what’s the connection between flow and theatre?

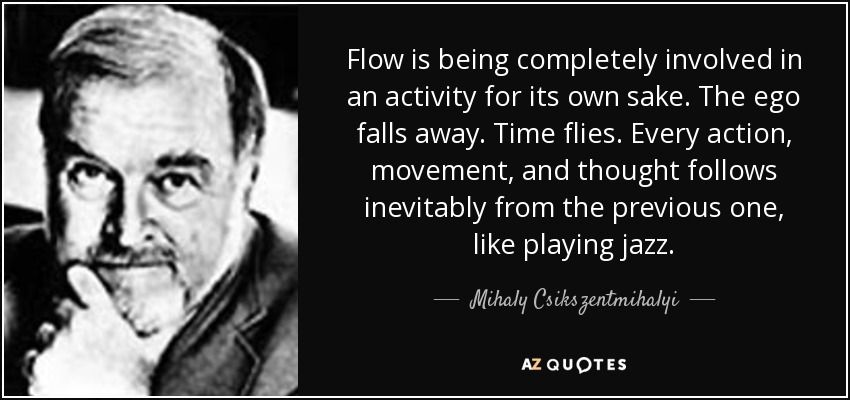

One answer to the question to ‘what is immersion?’ would be ‘flow’. The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihályi coined the term Flow, which is a state of complete absorption in the activity at hand. Csikszentmihályi claims that people are happiest when they are in the state of flow. He identified nine component elements of achieving Flow:

- There are clear goals every step of the way.

- There is immediate feedback to one’s actions.

- There is a balance between challenges and skills (so people feel stretched but not overwhelmed).

- Actions and awareness are merged (i.e. the mind is focused on what the body is doing – for example the rower who is completely focused on her stroke rather than the rower thinking about what to have for lunch).

- Distractions are excluded from consciousness.

- There is no worry of failure.

- Self-consciousness disappears.

- The sense of time becomes distorted (time seems to pass more quickly or sometimes a few seconds can feel much longer).

- The activity becomes autotelic – in other words it is pleasurable as an end in itself; we perceive it to have intrinsic value rather than something we are doing in order to achieve something else.

Of these, the first three things are elements that immersive theatre makers or video games designers can attempt to build in for their audience members.

The next six things are outcomes that ideally result from the successful design of the experience. Element 5 (distractions are excluded from consciousness) is something that theatre artists can help create, by asking audience members to turn off their mobile phones or asking the person who is drilling next door to pause until the end of the performance. But it is the first three elements that link immersion, flow and theatre.

Flow and theatre: a checklist for making immersive experiences

There are clear goals every step of the way.

Giving audience members clear goals is important if you want them to become absorbed. We think a lot about the instructions we give audience members and how to make them as clear and concise as possible. This is about being clear about what is expected of participants, which is especially important as -unlike for traditional theatre- there isn’t a singular behaviour code that is common to all immersive theatre experiences. It’s also about being clear about what the big goal is - for example ‘decide if the accused is innocent or guilty’ (as in FF's The Evidence Chamber). If people are unclear about what they are doing, they will feel awkward and embarrassed and this self-consciousness will inhibit their ability to enter a state of Flow - and therefore an obstacle to immersion.

There is immediate feedback to one’s actions.

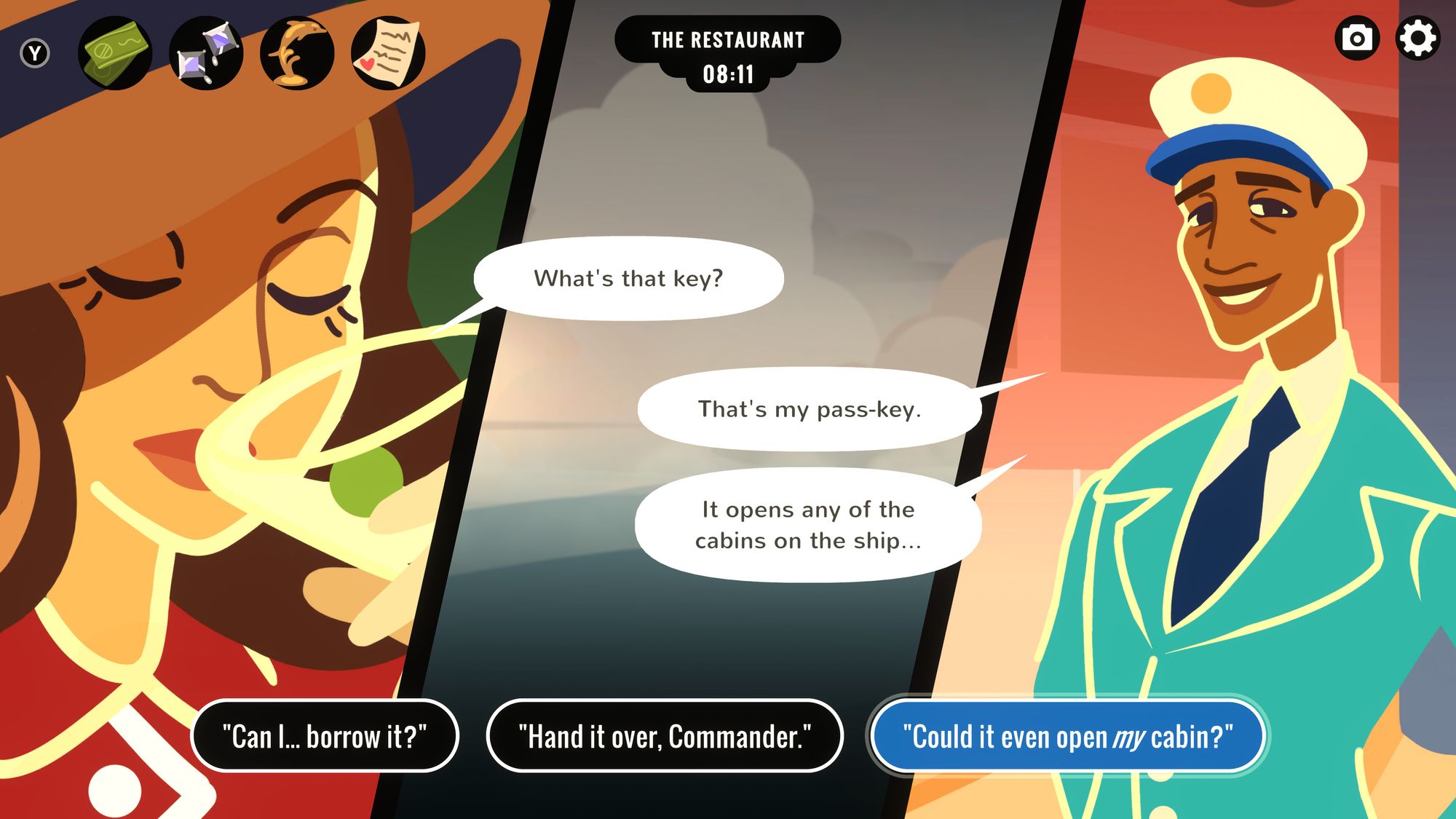

Having immediate feedback to your actions is also important. If you talk to a character in an immersive performance, do they respond? If they look panicked and like they haven’t expected you to ask that question, that gap in the feedback loop will remind of the fact that they’re an actor, not the world-famous jewellery thief. Feedback doesn’t always have to come from a human. A number of our pieces involve voting on various things: we immediately display voting results back to audience members, which allows them to see whether the points they made in the discussions swayed the votes of their fellow audience members.

There is a balance between challenges and skills

Achieving a balance where people feel stretched but not overwhelmed is something that many video games do very well: as you progress through different levels of a game, you get better and better - and the game challenges you more and more. This is often more challenging to achieve in an immersive theatre performance, especially where it’s a collective rather than individual experience, because different people will have different thresholds.

In FF’s work, we try to achieve a balance of challenge and skills in various ways. In The Evidence Chamber, audience members are presented with different types of evidence that point first in one direction (guilty/ not guilty) and then the other. They are processing information from a case that is becoming more complex.

We also use time limitations to stretch audience members. In Smoking Gun players have a limited ‘chat window’ of 30 minutes at the end of each day to share what they have each discovered during the day. Over the five days that the piece runs, the clues that they are given get increasingly hard to decipher, echoing the escalating challenges that video games provide. As immersive theatre-makers, there’s a lot we can learn from games.