Invisible Flock interview: The Networked Condition

'The Networked Condition: Environmental Impacts of Digital Cultural Production' is a collaborative research project exploring digital arts through an environmental lens. Here we chat to Invisible Flock.

At the start of 2020, Fast Familiar, Abandon Normal Devices and Arts Catalyst began The Networked Condition: Environmental Impacts of Digital Cultural Production, a collaborative research project exploring digital arts through an environmental lens. The project is part of The Accelerator Programme (led by Julie’s Bicycle and Arts Council England), which helps artists to advance their sustainable practice and share insights with their peers and the wider sector.

As part of The Networked Condition: Environmental Impacts of Digital Cultural Production, we’ve been speaking to artists and arts organisations whose work encompasses digital tools and environmental sustainability or activism, hoping to gain insight into a broad range of ideas and approaches. We’re writing up these case studies here as we go along, hoping that they’ll be a source of shared knowledge, inspiration or reflection for others too.

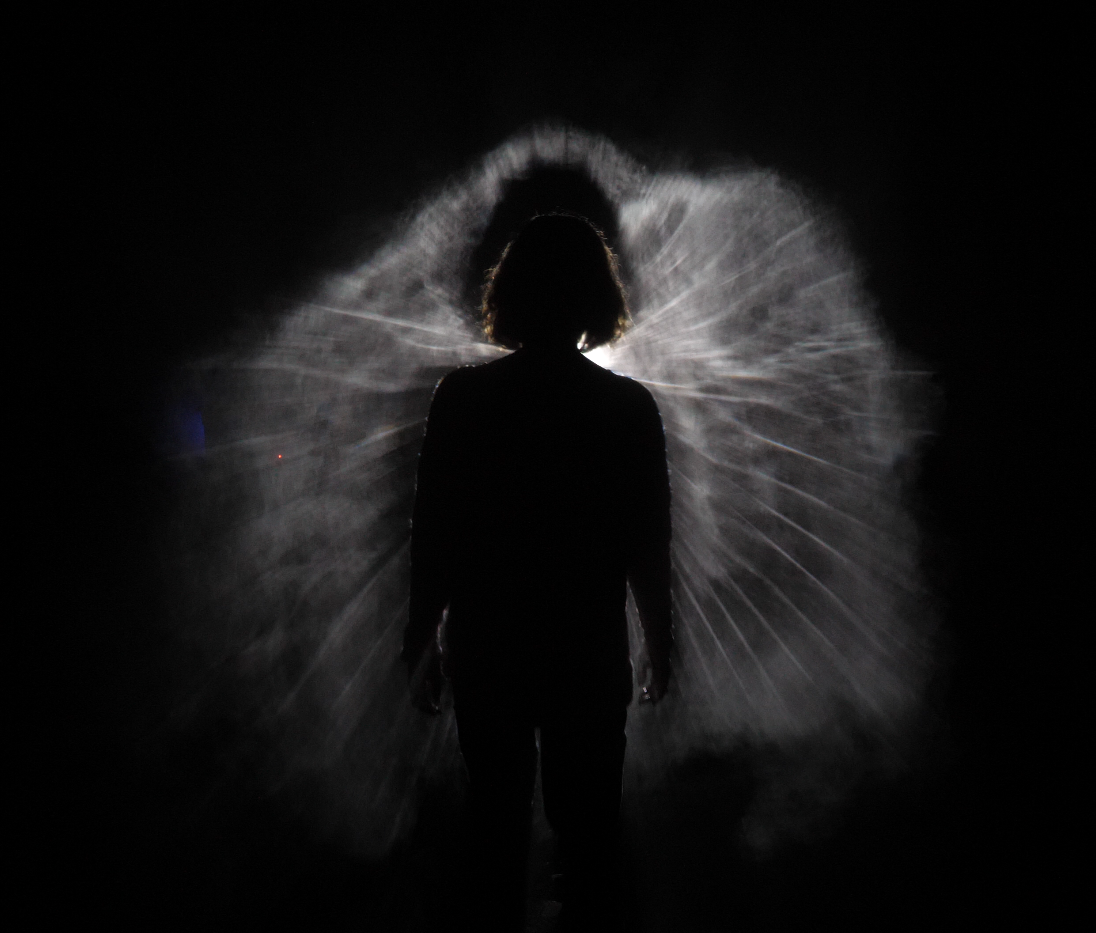

So, here’s the first with Invisible Flock, an award-winning interactive arts studio operating at the intersection of art and technology. Our conversation took place in spring 2020, which was of course a very particular time. We spoke to their Creative Director, Victoria Pratt, about one of their current projects, The Cost of Innovation – a three-year investigation into models and tools for technological and environmental innovation in the arts.

What is Invisible Flock?

Invisible Flock is a studio of cross-disciplinary artists, all with different skills and passions. We’re a core team of six, though that grows depending on the projects we are doing. We always work with technology; it’s very much a medium for us, a way to find solutions. We’re interested in it aesthetically, but that isn’t the driver. It’s what it can allow us to do with our work, how it allows us to expand our connection to people and communities. Our projects are quite varied but there are common threads: technology, research, and environment. More and more, as we all become increasingly aware of the ecological crisis that we face, we’ve tried to focus our practice on those challenges.

We have a studio here at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, which is quite new for us. We’re at an exciting point where we’re not in a city, so for the first time we can define our own sustainability initiative. It’s unusual for us to be so much in the UK, because a lot of our work for the past couple of years has taken place in Asia, looking at the Indonesian rainforest and human-elephant conflict.

It’s quite an interesting point to talk to you – four months into lockdown – I feel like we’re in a period of reflection, as many of us are, on what we’re doing, why, how, what it represents...

What is The Cost of Innovation project?

We’re at the beginning of three years of The Cost of Innovation project, working with several strands connected by three persistent observations:

1) We work with and support a lot of artists who want to use certain technologies but can’t access them.

2) There are phenomenal expenses involved when we try to access cutting-edge technologies.

3) Chasing the new through technological innovation is bad for the environment.

So on one hand, the project is about access and inclusivity: who is represented in the use of these tools, how can we ensure that more people (and different people) can use them? Artists are great at pushing, challenging and expanding the possibilities of these new technologies – but if they’re unable to access them, the commercial sector will race ahead and the arts just won’t keep up. So we’ve been looking into how we as a studio could purchase very high-end equipment and make it accessible to a broad range of artists, for free. We want to be able to house it, maintain it and re-use it. That last point is particularly important – before we became an Arts Council National Portfolio Organisation, we operated on a project-funded basis (like so many artists) and the amount of new products bought for each project was astonishing.

On the other hand, the project is crucially about technology’s cost to the environment. We’re very much at the beginning, but at the moment we’re figuring out how we can look critically at supply chains – every piece of equipment we have in the studio has taken a huge amount of energy to get here. It’s partly about finding solutions, but also about how we gain more knowledge in order to consider how we value things. It’s easy to sit in our studio with all our privilege and say we shouldn’t mine for these materials, but there’s a whole infrastructure of people who make their livings from these supply chains. It’s hugely complex. We’d like to open up the conversation by providing access to knowledge around it.

We’re approaching the project artistically because it’s the only way we know how. We’re collaborating with academic-thinker-designer Vladan Joler, of Share Lab who makes amazing maps of hidden infrastructures – and is helping us devise one for the iPod Shuffle. We’re taking it to pieces and looking at every component part of it, trying to trace the journeys and the people that got this tiny piece of technology into our studio. For example, the casing is made of aluminium, which is usually derived from bauxite, which is mined in tropical areas, then shipped to Iceland (because it has the right geothermal conditions for processing into aluminium), and then shipped to China for manufacturing. Thinking about that cargo, those ships, that journey – bringing forward those processes is really important. We also want to illuminate the human contact involved in these processes, so for each person involved in the Shuffle’s journey, we’re asking them to suggest a song that will then get added to a playlist on the Shuffle. So eventually there’ll be maybe 100 songs that go alongside these invisible supply chains about technology.

What are your methods for approaching the research?

We’re definitely starting from a place of self-critique, and we’re quite open to that – this research will uncover some horrible chains and processes for the technologies we’ve used. But it’s about asking how do we not just stand still and do nothing? How do I not just feel numb when everything I touch, everything I do has an element of destruction? I think that has to come from a place of analysing your own value systems and decision-making.

There’s also research to be done into how we can change our material operations as a studio: how can we invest in machines and fabrication processes that allow us to break down older materials that we have, instead of purchasing all the time? How can we become completely carbon-zero? The building runs on renewable energy already, but we’re doing some insulation work on the roof so that we’re wasting less energy. We’re also looking at more ways to remotely collaborate – for example, sending equipment to be used on other people’s projects, rather than sending ourselves.

How has the project gone so far?

We’re experimenting with different threads of what we can do, rather than sticking to one for now. It’s an ongoing process.

In year 1 we were focused on acquiring and making use of a LiDAR scanner. They cost around £60k so we were looking at how we use the kit across several of our own projects, but also make it available for other artists to use. It’s actually over at a research station in Finland at the moment, being used by scientists. It’s very interesting that we can just send this little piece of kit over to do work with other people. I suppose some universities might work like that already but it’s been new for us.

We were due to open our first residency programme a couple of months back, but most of this year is on hold because of Covid of course.

Next year we’re hoping to do local workshops with artists and networks so that we can develop the next part of the project. I can see the three years of the project really shifting and changing and turning and adapting – these longer-term research projects are so valuable in the arts at the moment because we’re obviously in completely uncharted territory. To champion the Arts Council for a moment: the project is running on a capital grant, which means we had to say that we’ll definitely spend x amount of money in three years, but in our application we said we don’t want to define what we spend that money on during year two and three, because we don’t know yet. And they gave us the money anyway.

What have you learnt from the project?

How restrictive it is to be green with technology – it’s really hard, and really expensive. Like hugely expensive. I’m saying things we all know, but that is a big challenge for the arts. It’s not that no one wants to be green, it’s the absolute expenditure that comes with – especially when you’re starting out. It’s suffocating. And maybe at a National Portfolio Organisation level or a regular funding body level, that’s what we need to help facilitate because you can’t do that with a £500 project budget.

What else? I think when Covid hit, I was very un-shocked by it. It was a weird feeling. Everyone around me was really panicking, but I felt like I’d been preparing for a crisis, I just didn’t know it would be this one. That’s the psychology of a few of us in the studio. I think it comes from constantly looking at how to continue as an artist.

How are you thinking in your approach to evaluation of the project?

I think it will be in the storytelling and conversations we have, rather than carbon metrics or anything like that. There will be numbers around how many artists used the kit, who got involved and all that stuff, but for me it’s more about seeing an ideological shift within our immediate sector, networks and funding bodies.

I think what culture does brilliantly is bring these conversations to the forefront. That’s one of the core aims of what we’re doing: how does this conversation enter the mainstream more quickly? How does culture become one of the shining beacons of this critique? How can we develop a language and tools to get at these issues?

Any tips for artists trying to do similar things?

I was talking to a collaborator Rudi Putra, who leads Forum Conservation Leuser, an NGO in Sumatra, where our ongoing human-elephant conflict project is, and I was asking what can young people in the UK do about these issues? His answer was just use less. We don’t need to consume everything, we don’t need to use everything. It was a really good provocation: how do you live with less, how do you make a more conscious choice around what you need?

But also, I think it’s about more research and development time. It takes time to work with technologies – to learn to use them properly, and make decisions about what suits you best. Otherwise it becomes a cycle of “well I tried that because I had to get my project out and then it didn’t work so I replaced it two weeks later with something else”. Frustratingly, that time is only enabled by funding. We need to be putting pressure on funding bodies to champion risk, research, and development – it’s their job to support artists and this is a huge part of the making process. There needs to be more support; so that there isn't just one dominant narrative or perspective, or story that we see made with these tools by those who can afford to use them.

April 2021 update: Invisible Flock will be joined by two artists in residence as part of The Cost of Innovation project:

Bhavani Esapathi or ‘B’ (Newcastle, UK) is a writer, maker & social-tech activist working in the intersections of art, health sciences & digital technology. Much of her work sheds light on hidden institutional practices which affect minority communities, those with chronic or invisible health conditions and [im]migrants . She also founded The Invisible Labs which is a global hub for those who experience autoimmune diseases. Organisations she has collaborated with include The British Council, The Royal Society for the Arts, Innovate UK, ACE, The Victoria & Albert Museum, The National Archives etc. Her invisible storytelling project won the WIRED Magazine’s ‘Creative Hack Award’ in the ‘most innovate idea as social response’ category in Tokyo, Japan.

As part of her residency at Invisible Flock, she is exploring ways to bring these three strands; access to adequate healthcare, migratory politics & climate action together in order visualise an inclusionary model to combat the current climate emergency.

Miia Kettunen (Rovaniemi, Finland) spent several years working as a freelance costume designer (MA), before developing a diverse way of project-oriented working as a visual artist. Her works are often site-specific with the consideration for the environment and derivatives to questions on how the work can originate from and communicate with the surrounding community. Her artistic techniques are evolving and transforming with each project she works on as she places much importance on the initiative nature of the work and her communal role as an artist

mediator.

In The Cost of Innovation residency she will study the subtle space and communication between human and nature and if the often missing sense of interconnectedness could be modulated into interconnecting points of coherence with the combined use of LiDAR technology and photography.