The big guide to public engagement and/ for artists

In this guide -based on interviews with some brilliant public engagement practitioners- we try to get to grips with what public engagement is, why it matters and how you know when it’s ‘working’. We also talk about what artists can bring to the process.

Intro

FF do a lot of work with researchers, helping them to share their work with new and different audiences, or to co-create new knowledge with people from outside their discipline.

This kind of activity is often described as ‘public engagement’, which is defined by the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE) as “the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public. Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit.”

Public engagement doesn’t always involve working with artists, but obviously that’s the point of view that we’ve experienced it from. We wanted to get -and share- a more complete picture. So I spent some time speaking to some of the genuinely brilliant people working in this area, to get their take (more info on our interviewees at the bottom of the guide).

In this guide, we try to get to grips with what public engagement is, why it matters and how you know when it’s ‘working’. We also talk about what artists can bring to the process.

You might also want to check out Nine top tips for artists working in public engagement, coming directly from our interviewees, and Public Engagement: the tricky stuff, which digs into the thornier questions that come out of this area of work.

What is public engagement?

At the heart of it, public engagement is about knowledge.

In its earliest form, it was more about getting knowledge created through research (often in universities) out into the wild. It happened at the end of the process, a kind of report to the public about what the researchers had been doing and what they’d found out. It might look like a public lecture, an experiment demonstration, or a pervasive game at a festival. We’ll call this knowledge dissemination.

As the field of public engagement matured, practice broadened from this ‘knowledge deficit mode;’ to activities where researchers were co-creating knowledge with non-researchers, rather than telling them after the fact about what they’d been up to. This might look like a co-design workshop, sessions with a patient advisory group, or an immersive experience situating members of the public as an ethics board in a hospital. We’ll call this knowledge co-creation.

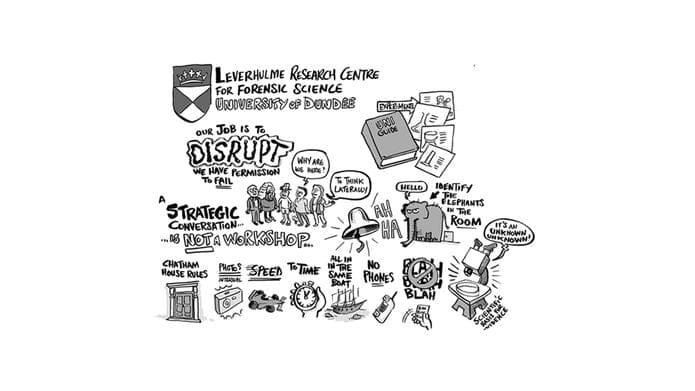

Of course, it’s not an either/ or: there’s a whole spectrum of activities and approaches between the public lecture and co-created knowledge. Simon Watt, Public Engagement Manager at the UCL Hawkes Institute, makes the case for “a mosaic approach”, combining discursive, two-way engagement, which reaches fewer people but leads to active change for researchers themselves, with one-way dissemination like large lectures. Both Simon and Heather Doran, Public Engagement Manager for the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science at the University of Dundee, another established research centre, talk about audiences going on a journey within their mosaic of provision, perhaps starting by attending a talk but progressing to taking a more involved role in the centres’s work, as part of a Patient Advisory Group or Citizen Jury. Knowledge dissemination can be a gateway drug to deeper knowledge intoxication.

Knowledge dissemination projects are often now regarded as ‘entry level’ for researchers too, with events like A Pint of Science or Soapbox Science giving them an opportunity to test how they might communicate their research to non-experts. These more one-way formats can allow them to get a taste of public engagement before committing to a full-on knowledge co-creation process - which is more demanding, not least for planning, as Jamie Upton, Senior Public Engagement Officer at The Royal Society describes, “You have to be designing your experiments and your whole engagement strategy for interrogating a question right at the beginning rather than after the fact.”

Why does public engagement exist?

Jamie Upton locates the rise of public engagement as a reaction to notable cases where great research was let down by poor communication in the 1990s and 2000s. “You can point to the landmark cases where amazing research was conducted but because the public engagement part of it was carried out so badly, it actually ended up setting back the progress of the research. GM -genetic modification- is probably the best example of that. So the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee report in 2000 basically said, this is awful, something should be done about this. And in fairness it was.”

Combined with that is a growing recognition that different bodies of knowledge exist, and not all of them are well represented within universities and research organisations. Traditional research generates technical knowledge which is, for example, essential for the diagnosis or treatment of cancer, but it doesn’t tell you what it’s like to receive that diagnosis or to go in for treatment. To understand that, you need to speak to people with lived experience. Public engagement exists to bring different bodies of knowledge together and support the people who hold them to listen, talk to, and understand each other.

Why is it important?

As well as bridging the divides between different knowledge systems, public engagement can ensure that research is taking place with an awareness of societal context. As Lucy Yates, Public Engagement Lead for the Sustainable and Healthy Interventions for Food (SHIFT) project at the University of Oxford, describes: “Structurally, for a long time research was separated from the public in terms of what drives the research agenda. It needs to take into account what is valuable to people and also the material circumstances of their lives.” Will Hunter, Creative Producer and PhD student at the University of Bristol, sees the current role of public engagement as most often “sense-checking”; that it rarely drives the research agenda but can prevent what happens within research organisations from being totally tone-deaf.

For Heather Doran, the need for non-specialists is about widening who has a stake in shaping the world we want to live in: “Research is one of the things that determines what our future looks like. It's really important that we get as many people with different opinions in the discussion because everyone's got an investment in what happens in the future.”

We live in an era of declining trust - which will further decline if people feel that our institutions don’t serve them. Rightwing populists seek to brand the media, the judiciary, large parts of our democracy and universities as ‘elitist’ and not working in the interests of ‘the people’. If public engagement grew out of a need to re-build trust in the early 2000s, it has never been more critical. All the public engagement professionals I interviewed spoke about it. For Simon Watt, it’s how he defined his work: “Public engagement is a two-way process aimed at making the work of institutions more trusted and trustworthy.” Simon’s statement implies transparency (“institutions are more trusted”) but also that research can be held to account and affected by the public (“institutions are more … trustworthy”). Public engagement is a way to ensure that research reflects public concerns - and can’t be regarded as irrelevant or elitist.

For Heather, universities have a unique role to play in halting the decline of trust. “Universities are still in a place where people trust them more than a lot of other organizations. Businesses have an agenda: they're making a product. They're making profit. Public sector organisations, like the police, have a remit.” Universities -not driven by the need for profit or a remit other than knowledge creation- can act as a neutral space with convening power over other stakeholders. This is what attracted Heather to her role at the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science at the University of Dundee: “A university can provide an open space for people to have difficult conversations because they're thinking about how things might be in ten, twenty, fifty years’ time, rather than the immediate impact.”

If all this sounds too ideological, there’s also another compelling case for why public engagement is important: it makes for better outputs, through informing them with different bodies of knowledge and societal concerns. And these research outputs aren't just academic papers or conference presentations or other ‘academic’-type things one might associate with universities. “Nearly everything we've got will start life through our universities. And I don't think that is really considered when people think about the outputs because it's not often the universities who are doing the final step. But it's based on work that universities and research will have done, and they’ll have trained most scientists working in industry,” explains Heather. You may not see a university name or crest on the box of antibiotics you’ve just been prescribed, or the machines building your kid’s new school, but they’ll have had a hand in developing them. And why would we not want these outputs to be supported by processes which make them the best possible?

So is this just market research/ focus groups?

Public engagement as a sense-checking methodology to ensure outputs are attractive and high-quality… it seems like we’ve drifted a long way from the lofty aims of knowledge sharing and creation. Lots of public engagement is funded by public money, so should it really be taking the role of processes we’d associate with the private sector, like market research or product development focus groups?

It’s tricky because a Patient Advisory Group is partly a focus group, but I think many of us -especially those with experience of being impacted by medical processes- would say that patients need a voice. Jamie Upton describes Cancer Research UK’s journey: “CRUK started with patient involvement in clinical trials but they've gradually brought patients and their families and carers into different aspects of their governance processes.” Surely it’s a positive step that people with lived experience of cancer are being consulted about all aspects of research?

But maybe this is an easy example. Maybe it depends on your standpoint on what is being researched, because at the end of the day, lots of public engagement is a form of market research or even market acceptability. If you have ethical reservations about what’s being developed, for example the rapid advance of artificial intelligence in many areas of our lives, you may find it worrying that research is taking place into how that advancement can be made more palatable or even attractive. But if all the research conducted by the SHIFT project at University of Oxford shows conclusively that eating meat at the volume we do in the Global North is bad for our health and for the planet, is it so bad to do activities that explore which framings will help different people reduce their meat consumption? The first example worries me but I’m totally behind (and involved in) the second - because of my views, values and experiences. There’s a point at which all this becomes ideological and much more thorny than it initially appears. That gets its own exploration here, as these are important questions for artists (and maybe anyone) to consider when entering the field.

What does ‘successful’ public engagement look like? How do you know it’s working?

Impact in general is incredibly hard to measure. I’ve written elsewhere about the challenges and dangers of measuring the impact of arts-based activities (which is my experience of public engagement). Almost everyone I spoke to talked about conversations they’d had or witnessed during public engagement events where someone seemed profoundly affected by the encounter - but this isn’t evidenceable as success (unless your metric is ‘people have good conversations’, which is perhaps an underrated achievement!)

Sometimes a metric of success is determined by a funder. The Wellcome Trust, until latterly a big player in the science public engagement landscape in the UK and funder of Lucy Yates’ (and our) work with SHIFT, is aiming to ‘change the national conversation.’ This begs the question: where is the national conversation taking place, and how do you know when you’re part of it - or even witnessing it? Legacy media is serving an increasingly small sliver of the population. The social media landscape has fragmented in recent years. Food (SHIFT’s area of research) is saturated with advertising - does something count as part of the national conversation if a food multinational has spent billions on putting it there? I simultaneously don’t know how you’d prove that you’d changed the national conversation and can point to movements which have (within the food space, the anti ultra-processed food lobby have gained absolute ubiquity). Answers on a postcard please.

For Heather Doran, working in a research centre with multi-year funding, one of the ways of measuring whether their public engagement model is working is to see whether people move through the mosaic, starting by attending an event which doesn’t even take place at the university but instead in a local pub or cafe, then perhaps an event at the university in a format which didn’t make huge demands on them (like a lecture), then -having built this trust- being open to deeper involvement.

For Simon Watt, success is as much about the journey his researchers go on as it is about the experience that the public have: “The unit of measurement is where everybody leaves the experience changed. A thing that surprises most of my researchers is that my evaluation of our audience is limited compared to my evaluation of them.” Simon’s mosaic of provision, with its different depths of engagement in different activities, also works for his researchers: “they develop the skills of talking about their research at the science fair and public lecture, to then be able to explain it more simply and effectively in the more co-created formats”.

If this nonhierarchicalness is an indicator of successful public engagement, it’s a tall order because it stands in contrast to the distribution of power and resources within the room, with the university and researchers often holding more power/ capital (however you measure that) than the non-researchers. A number of universities (or departments within them) have tried to implement structures to mitigate the inequality of the relationship, but it’s not without challenge. Jamie Upton could think of four examples of universities with dedicated spaces and processes for research co-production, which in itself speaks to the challenges: “All four of those examples are relatively well-funded Russell Group universities, which probably tells you something about the amount of money and strategic planning that's needed because you need also to say ‘this will exist for a minimum of five years’. Otherwise it just risks parachuting scientists in and then getting them out and being quite extractive.” All this activity takes place -as all my interviewees noted- against a background of reduction in funding to higher education.

So what’s the future of public engagement in the UK?

It’s probably not an understatement to say that in 2025, the UK higher education sector is in crisis. Not all research and public engagement takes place in university settings but a lot of it does. Universities (including Russell Group unis) are struggling to make budgets balance, impacted by reduced student numbers (especially international students) and less research funding. So what does this mean for public engagement?

There is definitely a trend towards knowledge co-creation over knowledge dissemination, with funders expecting this kind of public engagement activity to be written into bids. Conversely, researchers under increased work pressure (caused by the aforementioned crisis) have less time to do the kind of knowledge dissemination projects which don’t have earmarked resources attached. This is compounded by a reduced number of events where these activities could take place. Post-COVID and mid cost-of-living crisis, there simply are fewer audiences for events like Museum Lates. Venues like the Science Museum no longer run their Lates event monthly; this was previously a staple of ‘fun’ dissemination activities. While the shift to co-creation holds the promise of less hierarchical relationships between researchers and others, it also removes the gateway drug for researchers, as Jamie Upton describes: “It would be very hard to go from being a researcher who has never done any type of engagement at all to being one who is designing a citizen science project or a participatory research project.”

The Wellcome Trust have funded huge amounts of public engagement work in the UK, but they have now diverted their funding to projects in the Global South. A number of people I spoke to identified this as the single most impactful development for the future of public engagement in the UK.

But Heather Doran is hopeful, despite the balance in universities shifting towards teaching and away from research: “I don't think universities will ever stop doing public engagement. They won't because a lot of the best researchers realise that doing engagement is helpful for research and they want to do it.” Heather also speculated that in the future, more science public engagement will be led by charities and independent practitioners, rather than located so much in universities.

How do artists come into all this? Why work with them/ us?

So if there’s already two groups - researchers and non-researchers- involved in the complex processes of public engagement, why add another group -artists- into the mix?

For Heather Doran, it’s clear: “I think it's always the same thing. Artists make you think about things in a completely different way. They help make sure that you're not going down an obvious route.” She values artists in public engagement processes because of the questions they ask, and the way they don’t share assumptions commonly held by researchers and others within university systems.

For Simon Watt, it’s the discussions that art can provoke, in a slightly different way. “The oblique angle taken through an arts workshop means that people can talk about trauma indirectly.” Art and creative activities can provide ways for people to communicate the knowledge they hold in a way that is more on their own terms, and less ‘cold’ than other research methods might feel. It’s not really about the artistic output itself, it’s about the interactions it supports.

For Lucy Yates, the presence of artists changes the context: “it basically adds human connection.” She describes a pop-up museum created with artists in a shopping centre, and the way that members of the public stayed and also made return visits to engage with the activities and the artists. “They were emotionally engaged. They were interested. They were curious. They were being fed something and they wanted to engage in dialogue. They wanted to make things. They wanted to create.”

Jamie Upton sees the role of artists as the architects of a process which takes account of social dynamics, functioning as an effective interface between researchers and the public, ensuring good communication and capturing the interactions that take place. But it’s more than a social science experiment: “The arts side of things makes things softened and palatable and enjoyable. Quite frankly, engaging in a social science experiment that's just purely done as a social science experiment might be a bit dry and boring.” He also notes the power of an artistic, imaginative experience to “disarm” participants, meaning they’ll respond in a more honest way to whatever they’re presented with, thus avoiding the intention-behaviour gap.

And what’s our take? FF also talk a lot about the ways that narrative can be used to reduce the intention-behaviour gap. I completely agree that it’s about the process you can take people on, rather than the ‘artwork’ itself. And that (good) artists ask great questions. What I’d add is that art is a space which is outside real life so the possibilities are different. FF have always talked about art as a space where people can explore the stuff that feels too big for daily life, and rehearse new ways of thinking and being. That principle actually becomes more important when the big stuff is science that will have a profound impact on how we live in the future. I think an artistic or design approach can really support people through that process, because otherwise things like AI and climate change are actually pretty terrifying to think about.

Conclusion

Public engagement has changed a lot over time, and will continue to change - as it needs to, because it necessarily exists in dialogue with a wider societal context. There may well be less money in the future (*sigh*) but co-creating knowledge seems so useful (in so many ways) that it isn't going to disappear entirely.

Everyone agrees that artists have a lot to bring to the process. Looking back over what interviewees said, I’m struck that very little of this is about the actual making of the art, the painting of a picture or choreography of a dance. It’s about care and context and process and finding ways to support people to show up as the most human versions of themselves. It suggests that artists have an incredible range of skills that can be brought to other things.

And at a time when public trust in science is under assault from the populist right and our government’s vision of the future offers hope to so few, it seems like there could be worse places to apply that skillset.

Many thanks to the people who agreed to be interviewed for this piece. You can find out more below about the people who are directly quoted.

N.B. Quotes were taken from interviews but the views expressed might not share the full picture: this isn’t a full research study.

Heather Doran is Public Engagement Manager for the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science at the University of Dundee. She has over a decade of experience working in the area of public engagement and science communication. She sits on the Scientific Committee of the Public Communication of Science and Technology Network (PCST), an organisation that brings together science communication practitioners and science communication researchers to create connections and inform the practice of science communication around the world.

Will Hunter is a Creative Producer and PhD student at the University of Bristol. His research problematises the current management of relationships that form between the University of Bristol and creative and community partners in collaborative and co-produced research, largely by recognising how the impacts of neoliberal policy on 'the University' favours and drives specific forms of collaboration. He also has a decade of experience producing public engagement and art-science projects.

Jamie Upton is Senior Public Engagement Officer at the Royal Society. He's worked in science events for more than a decade, producing arts-science based exhibitions, workshops and performances. He's currently looking at the policy environment that different aspects of the public engagement system sit within, to find ways we can increase and improve the connections between science and society.

Simon Watt is Public Engagement Manager at the UCL Hawkes Institute. He has over 20 years’ experience working across public engagement and science communication. He has also written a Practical Guide to Science/ Art Collaborations.

Lucy Yates is Public Engagement Lead for the SHIFT project at the University of Oxford.