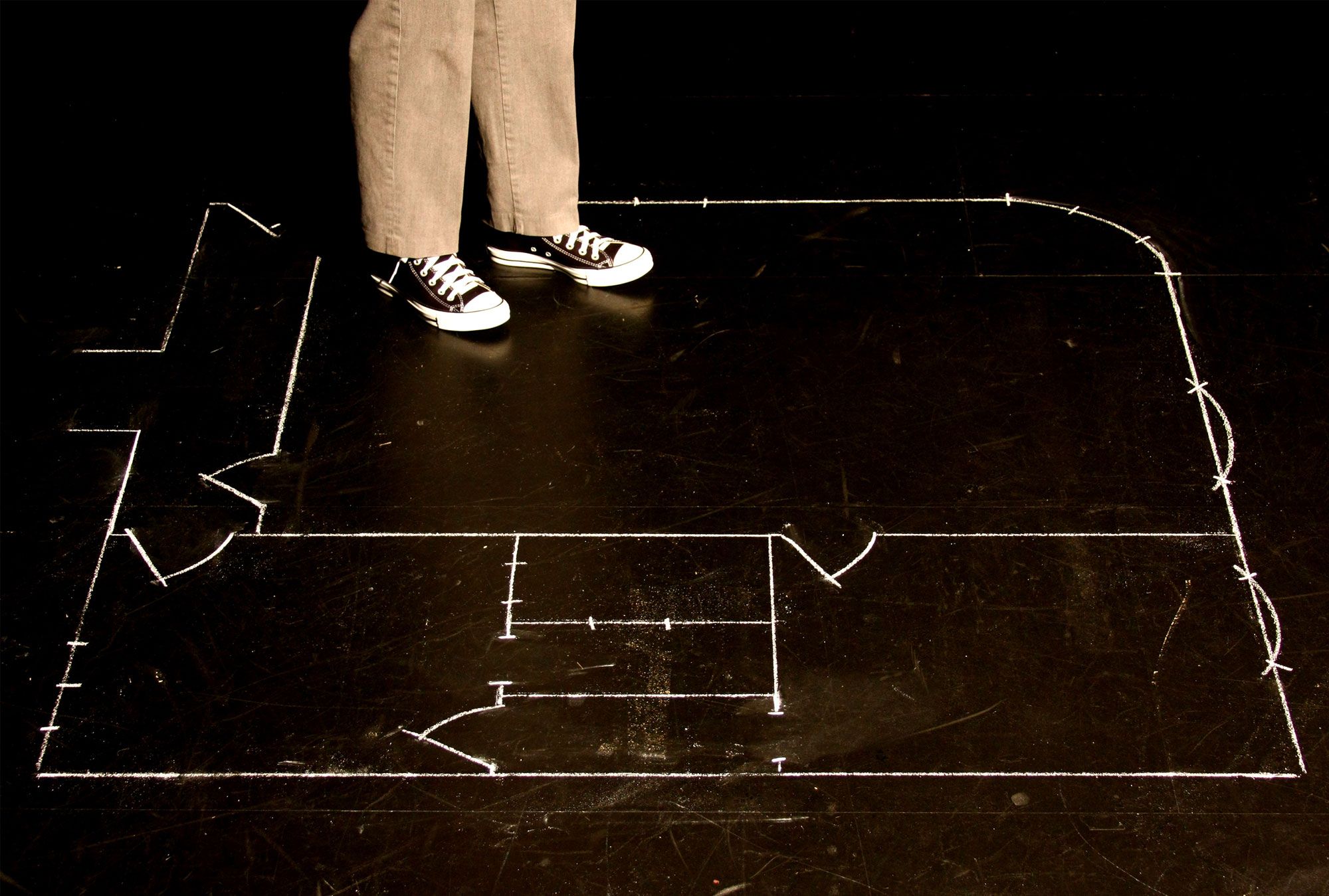

Putting the play into theatre

What do we really mean when we talk about playable theatre, immersive theatre, interactive theatre and the like? And what do we hope to get from works in these categories?

When we’re trying to describe what we do, particularly to theatre folk, we often end up describing it as 'audience-centric performance' or 'playable theatre'. 'Playable theatre' isn’t a term that we came up with; as far as I’m aware it was coined by Tassos Stevens of Coney to describe the sort of work that they make.

So what do we mean by playable theatre?

With most western theatre, you sit and watch the action unfold. Sometimes the performers pretend you’re not there and at other times they address you directly, but in general what’s expected of you as the audience member is to sit quietly (maybe laugh at appropriate moments) and clap at the end. This doesn’t mean that you are passive as an audience member - far from it. Often you’re following the story, imagining yourself in the shoes of the characters, thinking about what all of this might mean.

Playable theatre is different because you’re an audience member but also a player. As a player, the things you do are not just internal (like when watching other types of western theatre) but also external. These extra things can vary massively between different playable theatre pieces. In Coney’s Remote audience members vote for the character at various decision points by holding up one colour of card or another. In Seth Kriebel’s A House Repeated, the audience can make decisions about where to go next in the house, changing how the story unfolds. (These choices echo those available in some types of interactive fiction.)

In other playable theatre your actions as a player extend beyond merely making choices. In Coney’s Early Days of a Better Nation you're allocated a role when you arrive at the theatre, based on where in this fictional newly formed nation you live and what your priorities are. You then engage in debates with others groups, and internal wrangling within your own community about how much to compromise and how long to hold out to ensure your own interests and values are protected.

What's the difference between playable theatre and immersive theatre?

Broadly speaking, immersive theatre involves a set that surrounds and immerses an audience, who can wander around it quite freely. The most famous immersive theatre-makers are Punchdrunk, who have previously invited audiences into sets that took over the whole of Battersea Arts Centre, in productions such as Masque of the Red Death. In these shows you can choose to follow the main action as it travels through the building or you can peel off to explore quieter corners, but your choices won't influence what happens in the story - just how much of it you witness. Obviously, folk don’t always use 'playable theatre' and 'immersive theatre' with total precision, but this is my sense of the difference between them. Immersive theatre can be playable and playable theatre can be immersive, but it is perfectly possible for a work to be one of these things without also being the other.

So what happens in Fast Familiar’s playable theatre?

We’ve long been interested in seeing how far we can put the player or audience member at the heart of the action. That’s why we also sometimes refer to our work as "audience-centric performance". In Disaster Party (a project we made a few years ago), each audience member is given a role when they arrive at the theatre, along with some costume elements to wear and an MP3 player. The MP3 player feeds dialogue to you as the player and guides you about where to go and who to talk to. You gradually piece together who you are and what is going on. As the piece progresses, you have more and more freedom until in the final phase of the piece your character is interacting with other characters unguided.

In our courtroom dramas, The Justice Syndicate and The Evidence Chamber, there are only 12 audience members and each takes on the role of a juror in a complex case. After watching a range of witness testimonies and examining documents related to the case, players engage in a series of unguided discussions about the correct verdict, gradually moving towards a decision. In our whistleblower thriller, Smoking Gun, players pore over documents, photos and videos they've been sent during the course of the day and then text chat unguided for half an hour each evening, moving towards a decision about whether to go to the press with what they've discovered. In our newest work, National Elf Service, players experience an audio drama about disastrous events unfolding at the North Pole and collaborate with the rest of their team to solve a series of puzzles that help the characters save Christmas.

And why all the technology?

Playable theatre doesn’t necessarily need technology. The only technology that Seth Kriebel’s A House Repeated uses is normal theatre lighting. At Fast Familiar we became interested in using technology because we realised that not having live performers in the same room or online space as audience members was a way of encouraging players to have more agency and help them feel less embarrassed about what they were doing. If you’re interested, I unpacked this idea much more in an academic article earlier this year.

What’s the point of making theatre playable?

I think that playable theatre allows us to do different things with our audiences, things that tend not to be possible with non-playable theatre. In non-playable theatre, you can wonder what you might do in the situation the protagonist faces or learn from the mistakes they make. In playable theatre, you can find out what you actually do in a situation. This can be interesting and surprising. Many of our pieces involve a debrief after the main experience, an opportunity for you to reflect on what you did and why.

Playable theatre also provides an opportunity to practise new behaviours and test them out to see how they feel - a kind of rehearsal for reality. This was a big part of why we started making these works: we realised we were making theatre that was attempting to inspire action (around topics like climate change) so it would be useful to provide a space where people could practise that within the artwork itself.

We made The Justice Syndicate in 2017 in part because we wanted to create a space where a group of strangers could come together and have a conversation about important things. We were troubled by the polarised debates around Brexit and the Trump election and the deterioration of much political discussion into tweets and soundbites. Playable theatre can create a space that invites these sorts of meaningful interactions with strangers, and as makers we can minimise awkwardness through the fictional frame and how the experience is designed.

Playable theatre can also be really fun. Playing, after all, is a word we associate with having fun and the experience of taking part in a piece of theatre can be exciting, absorbing and energising. It has the potential to reach beyond more traditional theatre audiences to appeal to gamers, interactive fiction fans, and young people who are used to engaging with interactive dialogue-based media.

But is it really theatre?

We became much more cautious about describing what we do now as theatre a couple of years ago when we were pitching a project and the whole interview became about whether or not it was theatre - rather then what it was we were trying to do, whether or not it would work and whether or not audiences might like it. The honest answer is we really don’t care whether it's theatre as long as we are doing something powerful or fun to the people who experience it. People have posed similar questions about Huddersfield's Lawrence Batley Theatre’s online lockdown production of What a Carve Up, prompting Artistic Director Henry Filloux-Bennett to comment that he's "baffled by that need to pigeonhole stuff quite that much", which I really sympathise with. These debates might be interesting for reviewers and critics but I honestly think that most people don’t care as long as they're having an exciting or interesting experience.