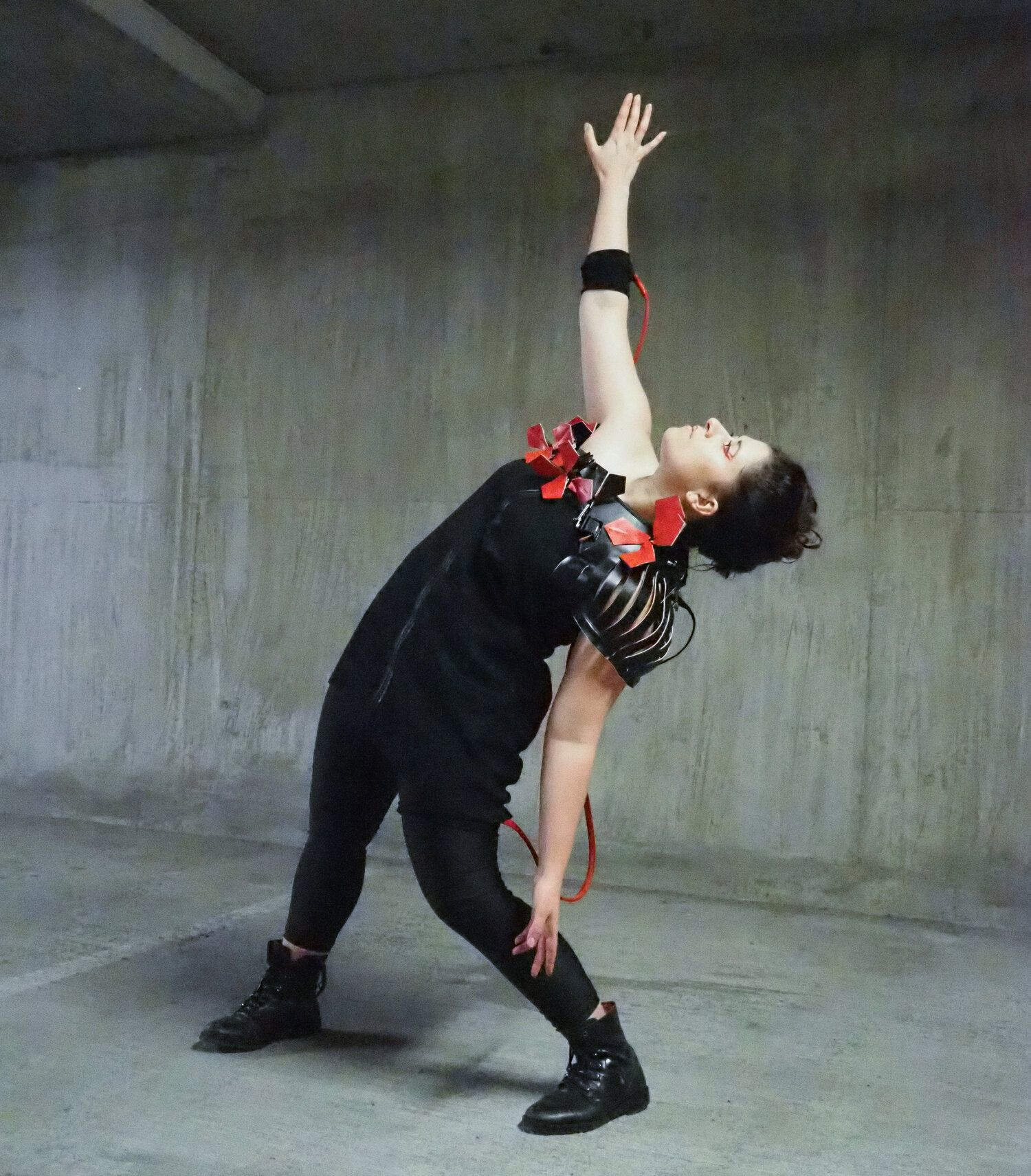

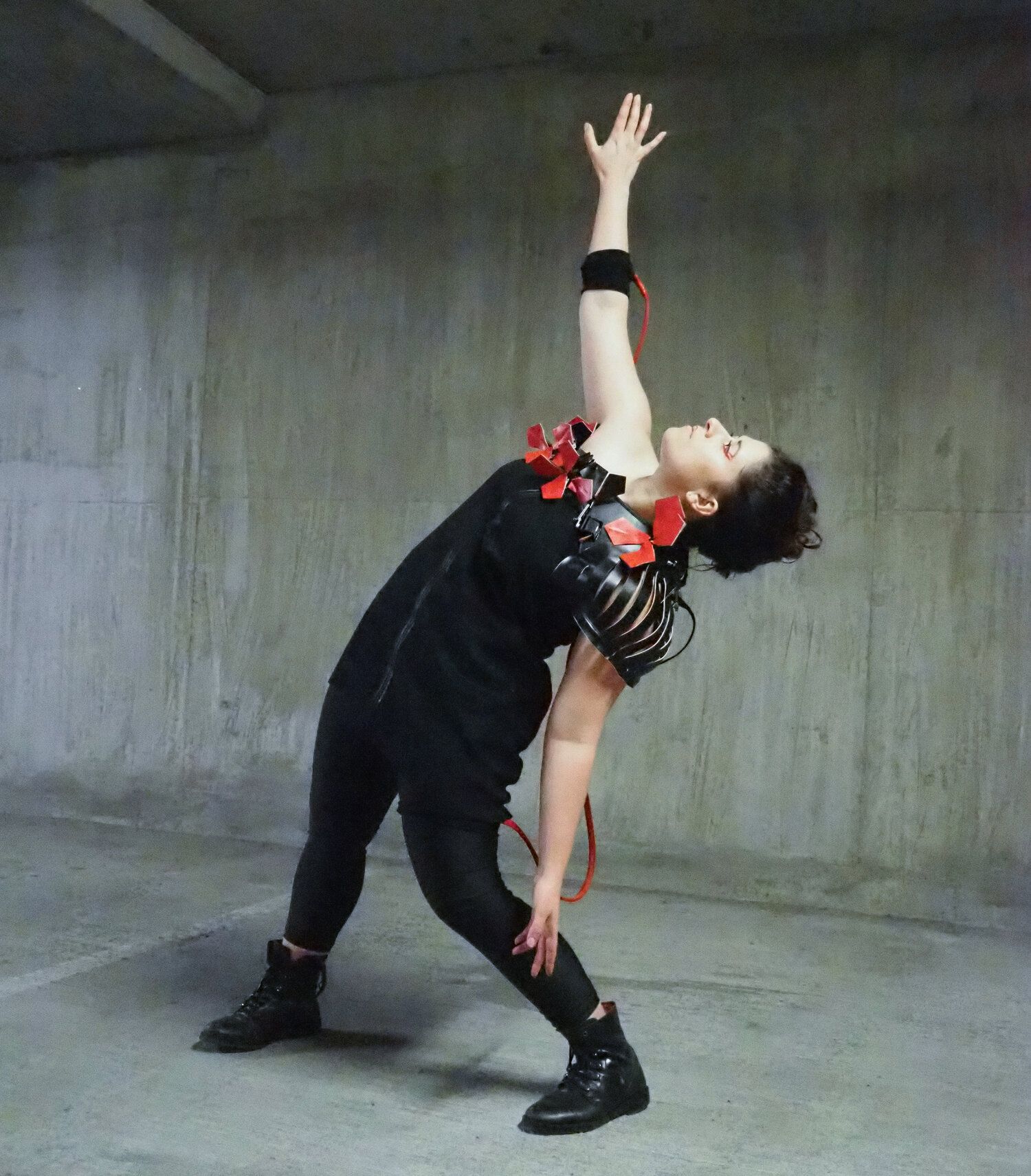

Collaborator interview: Clemence Debaig

In the first of our collaborator profiles/ interviews, Joe and I caught up with artist Clemence Debaig, who we worked with on The Curse of the Burial Dagger.

In the first of our collaborator profiles/ interviews, Joe and I caught up with Clemence Debaig, who we worked with on The Curse of the Burial Dagger.

Clemence has a long list of job titles: dance artist, interaction designer, creative technologist, artistic director of Unwired Dance Theatre (which she founded), and lecturer and researcher at Goldsmiths. The thread that links everything she does is a passion for choreographing audience interactions - so even if dance is her medium, she’s as interested in how the audience interact with the piece as she is in the movement practice.

One of the reasons we really like working with Clemence is how she thinks about an artwork on multiple levels simultaneously. Her journey into programming -which wasn’t a direct one- has really affected how she approaches it. Her background as a UX and service designer (working with dev teams but not doing the actual programming, unlike now) meant that thinking in systems and flows was already part of her daily life. Her dance experience meant she was used to thinking in terms of spatial awareness and embodied interactions. These perspectives inform how she creates installations but also work for screens: “There's a consideration of the context. Even if you’re going to interact on the screen, there's life happening around you. Where are you sitting? Which device are you going to use? Are you going to have your 5 year old child talking to you in parallel? So I’m considering the bigger picture of that experience.”

Before the pandemic Clemence was working with technology within a face-to-face performance context - as an enabler of interactions between the audience and the performance. When the pandemic started, she realised that the technology would now need to be the way that the audience would access the piece. She started exploring web technologies and virtual reality -“because it was a necessity - and I was bored and had access to a headset”- and started finding new forms of performance. “I was like, this is a full playground for me because everything can be invented, and for me being passionate about creating new types of audience interaction and challenging the way we interact when it's mediated by technology - this is so much fun.”

Like many artists during the pandemic, Clemence found herself seeking community online - and finding that the world had got smaller -or at least more connected- in some ways. “I was listening to the No Proscenium podcast, and very diligently writing down the names of the people I should follow on Twitter, and followed [artist, actor and VR creator] Brendan [Bradley], shared or liked one of his tweets, and then instantly he DM-ed me and he said, I've just seen your website. Your work is awesome. We're doing this festival in Web XR in two weeks. You want to jump in? I said yes because you don't say no to things like this.”

Throughout the last 18 months, I’ve found Clemence’s tenacity and innovativeness inspiring. I wanted to know if she felt the period had changed her as an artist. “Completely, I feel I am more self sufficient, because -as a one woman band- I had to find so many solutions to so many challenges from marketing to soldering and then performing in my living room. And oh hey I need a green screen. OK I'm gonna go on eBay and figure out how to use a green screen. So I feel like I can overcome any challenges and I think as an artist that's quite reassuring.” But she isn’t glorifying the experience: “It’s also exhausting.” Throughout our conversation I’m struck by how much of a different place Clemence and Unwired Dance are in, compared to March 2019. This is a period when some artists have -through their own determination- fast-tracked themselves from emerging to expert, and I hope the industry recognises that. The ‘no theatre during the pandemic’ narrative really doesn’t recognise the journey that artists like Clemence have been on.

In a way that really resonates with our experience, Clemence found the absence of organisations liberating in some ways. (Certainly from our perspective, it felt like the rule book had been suspended, and the people who told you what to do and gave you the structures to fit inside had gone home.) The absence of open calls and programming priorities helped Clemence clarify some things about her practice. “In terms of the type of things I tend to explore, it’s around themes of empathy, control and harassment, and I realized that was a thread throughout all my pieces. The pandemic helped me reflect on that. I’ve also realised that I’m not an expert in any particular technology, but what I'm really good at is building complex architectures and connecting things together. I’ve realised that it is my angle in this complex industry.”

Clemence’s attitude to her ‘past life’ as a UX and service designer also changed. In this industry, there can be almost a sense of shame in admitting that you didn’t emerge from the womb as a fully functioning artist with a singular focus. “I used to be reluctant to mention it because I wanted to pretend that I've done this for 10 years. But my past career was scaffolding for what I'm doing now - it prepared me to do something quite unique now.”

Clemence’s top 3 bits of advice for going back to physical installations

1. Don’t underestimate the time it will take to install a physical installation.

There’ll be all sorts of things you didn’t anticipate. Where's the plug? How long does my extension lead need to be? Ohh, the ceiling is higher than I thought so I didn't calculate my projector angle properly. I thought I could drill in this wall, but they are not allowing me to drill. So plan it and ask yourself the right questions and then plan for this to fail and then give yourself 3 more days.

2. It will take trial and error to understand how people are going to place themselves in the space.

You might think that your artwork needs to be seen a certain way, but you forgot that someone is going to walk through and have a look at the back. Or maybe they're not gonna understand and they're going to stand somewhere where they miss the full thing. Over time you grow more spatial awareness but you can also prototype it - model it in cardboard, put it in Blender, use Lego.

3. Watch people interact with your thing

That's the best learning! I have that piece that I presented for the second time in the Oxo tower, it was very different to the first space I had used. In the Oxo tower it was a very open space, so all the natural borders between the performer and audience [that had existed in the first space] had gone. Also it was in a group exhibition, so a lot of things were happening around it. People were missing the buttons because there was so much happening around it: they were like, OK, there's a person on the floor - that must be the performance. It was more of a contemporary art context. When you’re exhibiting with other interactive pieces, people tend to be like, oh, there's a button I'm going to click on it. If you're in the middle of paintings, no one is going to touch it, so I ended up doing two things. I put a spotlight shining on the buttons and a sign on the buttons saying ‘touch me’ - because everything else was like 'don't touch’ but this one you could touch, so I had to indicate that. You just have to observe people and see how they are interacting with the space and then move things around a little bit and readjust.

Clemence is optimistic about how our more general learnings during the pandemic might support more ambitious work to be created in the future - both for face-to-face and online. “People are less scared of using technology in different contexts. I remember two years ago when I was starting looking at using cell phones in performances. That would have required a lot of onboarding and a lot of being like OK, we're gonna spend the first ten minutes getting you connected to the Wi-Fi. Now I feel like it's gonna be a little bit smoother and people are not going to be panicked if they have to use their own device or interact with technology. And that's pretty exciting.”

So how does Clemence continue making ground-breaking work and building on all the learning she’s done during the last 18 months - what does she need to do that? “Money,” she says, “Funding opportunities are rare, and they're long and painful, and they don't fit the time frame I'm working on when it comes to technology.” She describes how there’ll be a call-out in July for a festival that happens in October - which just doesn’t give enough time to fundraise for -let alone make- the project. And even if there is time to fundraise, it’s so often outcomes-driven and the budget just doesn’t leave room for the kind of R&D that’s needed when you’re working with technology. So R&D ends up being done in personal time - which is a shrinking commodity. “I end up having so many jobs on top of this because I also need to pay the bills and I'm lucky enough that I have enough skills to find those jobs, so I can't complain too much, but at the same time I end up doing the things I really want to do -and that will be meaningful- in between meetings and after work because I can't find this sustainable funding.”

Talking to Clemence -and having experienced the quality and professionalism of her work as a collaborator- I’m struck by how unfair this all seems. Throughout the pandemic, Unwired Dance have pivoted, adapted, built audiences and done all those other things that you’re meant to do - and it’s still this hard to work out what a sustainable -and perhaps even scalable- business model could be. I’m sure that Clemence will make it work, through a deep determination, resourcefulness and commitment to the work, but what if it didn’t need to be accompanied by a high level of stress and anxiety? If the arts sector in the UK is serious about innovation, it needs to find ways of supporting people like Clemence.