What is the responsibility of the artist? Audience-centric theatre outside its comfort zone

A ‘literature review’ of audience-centric work that sits outside the comfort zone, including artworks by Davis Freeman and Jamal Harewood that are some of the most powerful experiences I’ve had in theatres.

You can listen to Rachel reading the full post here…

I talk and write a lot about artists’ responsibilities to the people who are involved in the participatory art that we create. And it’s really hard to get this right, so I could understand if a desire to avoid experiences which are harmful for audiences translates into making a certain tone of work - essentially experiences that don’t explore the darker or more challenging aspects of human experience. Experiences which avoid audience discomfort.

In the kind of art that people don’t take part in (or take part in an imagination/ empathy-based way) there is a whole spectrum of emotions: there are plays that make you laugh and plays that make you cry or get very angry, paintings depicting the best bits of humanity and the atrocities we commit. In interactive or audience-centric work, I think the bit of the spectrum we explore is narrower: people have a nice time, within a microcosm which is probably more utopian than daily life. And maybe this is ok. Daily life can be pretty rough. Why would we as artists want to make anyone re-live trauma or other terrible things?

I used to think there was huge virtue in artworks which held a mirror up to society and showed the bad things. But I wonder if that makes an assumption about your audience - that they won’t be painfully aware of the bad things because they have to endure them on a daily basis. If they are negotiating racism/ ableism/ any other discrimination every second of their lives, what do they gain from reliving it in an ‘artistic’ space? And yet, I want there to be ways for audience-centric work to inspire/ provoke a whole range of thoughts and feelings, including audience discomfort. So this is a bit of a ‘literature review’ of work that sits outside the comfortable space.

No time to finish reading this now, or want it as a document to keep?

Pop your email in below and it’s yours!

Santiago Sierra - various works

When I first read Clare Bishop’s book Artificial Hells, I was fascinated to read about the work of Spanish artist Santiago Sierra. (Disclaimer: Unlike the other two artists I’m going to mention, I’ve never experienced it first hand.) A lot of Santiago Sierra’s work explores the idea that everyone and everything has a price - and that social and political conditions result in a massive disparity between different people’s prices. In his work 160 cm Line Tattooed on Four People he paid 4 people to have a line tattoed on their backs, and they stood there in the gallery, side by side. (In some exhibitions there were photographs of this rather than the people.)

In Workers Who Cannot Be Paid, Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes a series of large cardboard boxes stood in the gallery space; the artwork was playing on the status of some immigrants in Germany (in 2000) who were legally prevented from taking paid employment – and simultaneously vilified for sponging off the state. In much of Santiago Sierra’s work there are people taking part in the exhibition, paid to endure arguably dehumanising activity; other people take part by paying to look at the people who have been paid for the dehumanising activity.

For the 2003 Venice Biennale, he made a piece called Wall Enclosing a Space. It involved sealing off the pavilion's interior with concrete blocks from floor to ceiling. On entering the building, viewers were confronted by a wall that prevented them from getting to the galleries. Visitors carrying a Spanish passport were invited to enter the space via the back of the building, where two immigration officers were checking passports. All non-Spanish nationals were denied entry to the pavilion. Sierra, along with other artists like Thomas Hirschhorn, make work which requires people to take part - but simultaneously problematises the act of taking part - both in the artwork and the society on which it comments.

I tried very hard to think of examples of work taking this approach which comes from a performance or theatre background, rather than gallery-based practice. I could only think of a couple of examples of participatory art that I saw in theatres. (Both are by men, I’m not sure if that’s about my theatre attendance habits or something else.)

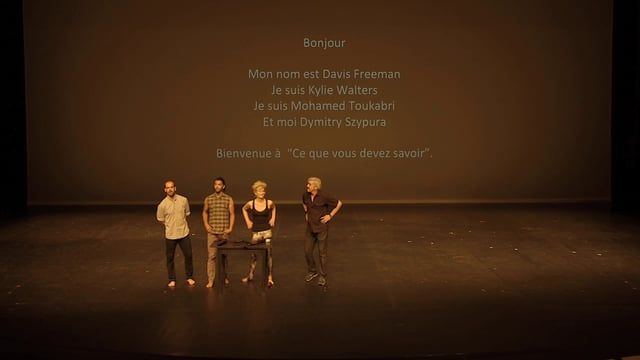

Davis Freeman - What you need to know

In January 2015, I saw a piece called What you need to know by an artist called Davis Freeman, at the Kaiitheater in Brussels. It was12 minutes long and maybe the most complete piece of theatre I’ve seen - in the sense that nothing was there that didn’t need to be, and everything that was in it was essential. I’ve never seen it advertised anywhere else, and to my knowledge, it hasn’t been on in the UK.

In What you need to know Davis (who is a tall white man in his 50s) comes onto an empty stage with 3 dancers. Each dancer is holding a gun, which they put on the floor at the front of the stage near the audience. Davis tells the audience that he’s going to explain how each of the three guns work. They’re each a different type of gun that was used in a real life shooting - Columbine and a couple of others. Davis explains that there was a kid at Columbine who got hold one of the guns but didn’t know where the safety catch was, so couldn’t use it to defend himself. So that’s why we should know how they work, he says - and he explains super dispassionately, while the dancers dance around behind him. And then he says, you should practice, because you probably don’t have these guns at home - so we can do that now. And a moving target is much better, so we’ll use the dancers.

He invites people from the audience to come and shoot the dancers... and I became really conscious -he’d introduced them before- that one is called Mohammed, one is a black guy and one is a woman. As the individual audience members come up, he asks them which dancer they’d like to shoot and explains what to do. It turned out that all the people who volunteered were white guys. They, and the rest of the audience, were sort of laughing, sort of incredibly uncomfortable. Davis was calm and dispassionate and the tone - of ‘this is a great opportunity to learn how to do this now...’ was very disconcerting. And although the people onstage - the shooters- were the ones most obviously active, it was most definitely an audience-centric piece of art.

Then Davis invited a 4th person to come and shoot him. He gave the guy the gun and asked him to wait a moment until I got to the middle of the space and turned around. And then he walked to the middle of the space and as he turned, pulled a Stanley knife out of his pocket and ran at the guy yelling. But as he turned, the guy said ‘I can’t do this’, put the gun down, and ran off the stage. I don’t know what would have happened if he had had shot Davis - or how common it was for that to happen. I haven’t done it justice in describing it, but this piece, and the way it centred the audience’s discomfort, raised some massive questions for me. It was a profoundly uncomfortable experience to be part of and a brilliant piece of art.

Jamal Harewood - The Privileged

The other piece of audience-centric theatre that problematised the act of taking part was a piece called The Privileged by Jamal Harewood, which is another of the most powerful artworks I’ve ever seen. I saw it in 2018 and I’ve since met Jamal and had the good fortune to talk to him about it. The below contains spoilers so if you’re planning to experience the artwork, don’t read on.

It was a Tuesday and it had just started snowing. Later we’ll call this patch of weather the ‘beast from the east’ but right now I -a Southerner- am just taking it at face value as a winter in Newcastle. I am waiting to see The Privileged at Alphabetti theatre. My friend, who is meant to be seeing the show with me, texts to say that the Coast Road is already a mess and she doesn’t want to risk driving in to town. Fair enough, I think, even walking ten minutes from the office was not fun. So I’ll see the show on my own.

I’ve heard good things about it, although I couldn’t tell you exactly what they were. I’ve heard it’s kind of risky, and kind of about race. I haven’t read reviews. It’s cold in the theatre bar.

When we go into the theatre, the audience is small. There’s two people I know, I was in a workshop on how to GDPR-proof your theatre company with them (fun times). There is a couple, he has a beer and looks like he was wearing a tie until just now, she is also dressed smartly. There’s two women I don’t know, I don’t remember anything about them. I remember seven people. Maybe there was also an usher who sat in. We were all white. We sat spread out around the auditorium, which is four sides around a stage area. There were bits of chicken, bones and stuff, on the stage area. I remember feeling cold and a bit sick, thinking about the snow and not wanting to get stuck in town, and guiltily hoping that the show is short.

A black man in a polar bear costume comes on, he is crawling on all fours. I don’t remember how we got instructions - I think there were envelopes with numbers on them on some of the seats. I think we figure out that we’re meant to open them and read them out… half of us do work in interactive theatre after all. I don’t remember what the initial instructions are, maybe to stroke the bear. The bear is called Cuddles. In any case, there are some instructions which we follow, dutifully. We are an English participatory audience after all, we want to get it right. It is super awkward. I don’t know if it was more awkward or less because there so few of us.

At some point there is a big carton of fried chicken brought in and we have an instruction to feed Cuddles. Cuddles doesn’t want to eat it. Some people try to feed him and bits of chicken get matted into the furry polar bear head. When Cuddles is escaping being fed, he crawls away fast and the actor’s knees bash on the floor. Bits of the costume come off and we can see more of the actor underneath it. I remember feeling worried for the actor but also that this is Jamal, who made the show, so he must be ok with it - it’s not like some poor guy being paid Equity minimum to get mauled and smash himself up. I don’t know why that changes things. It probably shouldn’t.

Basically stuff escalates. We, the white audience, are being asked to abuse this black guy dressed as a polar bear. The fried chicken evokes racist stereotypes. There’s other stuff that I can’t remember now. As a participatory theatre maker, I’m angry - we the audience are being put in a place where we’re either complicit with racism or the show can’t happen. I remember looking at the other theatre-makers in the room and seeing them making that same trade-off - wanting to be the Good Audience Member but also knowing what we’re part of.

I leave. I think there is some kind of semi-violent scuffle and I just stand up and say, sorry I don’t want to be part of this, and I walk out. Maybe it’s because I don’t want to be complicit. But maybe because it’s because the chicken makes me feel sick or I’m cold or worried about the snow.

I remember being really angry. I think about the show a lot and it makes me angry each time I do. What was I supposed to do? Stay and rub chicken in Jamal’s face and be part of overt racism? Or confirm my privilege - because I, as a white person, get to walk away whenever I want. Me walking away doesn’t stop the racism, it just means I don’t have to deal with it. I’m angry with Jamal. Smart show but he broke trust with his audience in some way that I don’t agree with. Or maybe I’m angry because what the show achieved was unsettling.

No one I know tweets about the show so I don’t have anyone to compare my experience with. It’s on maybe two more nights. I am annoyed I missed the post-show talk. Maybe I should have waited in the bar until it finished. I wonder how it would have finished. I think about Jamal in Newcastle in the snow getting small audiences for a show that must be breaking him. But I am still angry. Or maybe it’s the sound of white fragility. I’m so angry with Jamal.

It’s not until two years later that I stop being angry, because I realise there was an option open to me that would have worked with the show and worked for me. I think the penny drops because I’m thinking about solidarity and what it actually means. Instead of just leaving, I should have stood up and said, so are any of us ok with this? And convinced everyone to leave. My reasons for not doing that -I don’t want to impact negatively on someone else’s evening (beer dude seems ok, puzzled but not upset), I don’t want people in my industry to think badly of me, a newcomer to this city- should have been outweighed by knowing that what we were complicit in was wrong.

I wonder if anyone ever did that. I wonder what it was like for people of colour watching. Did they feel like white people were looking at them, as if their presence was legitimising what was happening? What did they do? Is it messed up that I feel like I would have taken my cue from them? I genuinely have thought about this show maybe more than any other I’ve seen. In so many ways it was such a perfect piece of participatory art that problematised the nature of taking part. It existed in such a different tone to so much audience-centric performance - we weren’t trying to help someone or to work together. We weren’t being entertained. What Jamal created was a testament to the incredible power that audience-centric performance can have and an inspiration to find ways to take audiences to challenging places.