10 things we learnt about access (in the broadest sense) while making The Evidence Chamber

We wanted to share what we learned, in the hopes that it will be of use to other people trying to make for digital space in an equitable/ inclusive way. We got some things right and some things... less right.

We recently completed a 3 week run of our online courtroom show, The Evidence Chamber. Here's some things we learned...

1. You will exclude people if you make work with technology

First, I want to acknowledge the barriers to access. In order to play The Evidence Chamber, you need a computer (not a tablet or phone) and decent WIFI. Not everyone has this. In Byker, two metro stops from where we lived outside Newcastle (and home of the legendary Grove for all you children of the 90s), there is, on average, 1 smartphone and 0 computers per 7 people. None of those people could have played The Evidence Chamber. There is a bigger conversation to be had about ‘digital democracy’ - but also infrastructure in general. The architecture of The Evidence Chamber is a computer and need for internet - just like the architecture for traditional theatre is a building that you have to be able to access. This isn’t just about getting in the building, it’s about getting there and getting home. We had a production assistant who lived in a town outside Newcastle called Corbridge. He didn’t drive. The last train from Newcastle to Corbridge leaves at 21.25, making it impossible to see a 2 hr show at any of the city’s venues and get home. So let’s have a conversation about all the infrastructure we don’t have. I’m not saying this to deflect from our own digital exclusions, but to illustrate that it’s complicated.

2. Making yourself available can make the work more approachable

To make it less scary, we had an email and phone number that we encouraged people to use to contact us with any concerns about technology. Lots of people did this prior to buying tickets, as well as just before and during the show. Joe built tools so that he could diagnose problems remotely - and sometimes even fix them before players noticed.

3. You can’t build digital tools for access if you don’t have enough time

We tried to build various access features (e.g. embedded AI captioning for discussions) into the platform, while trying to build it, on a very tight schedule. It wasn’t achievable. Now we have the platform we can look at improving access. We were also trying to build access features without having consulted users on what would be useful. In short, we didn’t have enough time. We’ve learnt to allow more. (All the videos were captioned and we saw high use of this feature… which might have had something to do with Dundonian accents.)

4. Think about what you feel OK with people experiencing in remote locations

We chose to use The Evidence Chamber as the first piece we did in this remote courtroom format. We could have used The Justice Syndicate, which is a piece we’ve done multiple times with face-to-face audiences and has received some critical acclaim. But we decided against this: The Justice Syndicate is a sexual assault case, with some tough content. Discussions can be robust and potentially difficult. We imagined someone playing, it affecting them profoundly and then being sat alone in their flat afterwards with all those feelings. We didn’t want that. The Evidence Chamber is a murder but the nature of player interactions is collaborating to piece together a story, rather than arguing about a moral dilemma. Some audiences wanted to argue more than the piece asked, which is an interesting thing to observe about the interactions people expect. Unlike with The Justice Syndicate, we didn’t put a content warning on The Evidence Chamber - and we should have. An audience member pulled us up on it, and we added it - but we should have had it from the start.

5. Accountable online spaces require careful crafting

In the run-up to the show, we were working on our accountability policy, which you can find here. We had ‘In purchasing a ticket to The Evidence Chamber, you are agreeing to abide by our Safer Spaces policy’ on the Eventbrite page with link. Some people read the document (they told us), but I would imagine not all. We planned to read the Safer Spaces policy at the start of each show. In the end, we chickened out because onboarding already took a long time and we were worried it might scare people into silence. I don’t think that was the right thing to do. I don’t really know what we should have done. It’s something we’re working on.

(I should say there is a moderator and an in-game mechanism for accountability, so we weren’t totally leaving people to their own devices.)

6. Using temporary names can change group dynamics

During the discussion sections in the game, players use a video chat platform. Beneath each person’s video is the label ‘Juror X’ - with a number from 1 to 12, and the pronouns that the person has chosen. We could have had the person’s name - they could have entered it at the same time as choosing their pronouns. However we had feedback from people with ‘difficult’ names that they felt during discussions (face-to-face, in other situations, before the pandemic) that they weren’t called on because the person chairing the discussion (who was often white and English) was worried they would pronounce the ‘difficult’ name wrong. So although it is slightly weird to be referred to as a number, we decided this was preferable to a situation where people with English names got more airtime.

7. Internet service providers lie about their WiFi speeds

It’s not much fun trying to explain this to someone who has in all good faith bought a ticket thinking their internet is fine. We did provide a link for people to test but not everyone does - and, not to get too technical, there can be a massive difference between upload and download speed that messes things up. What we’d like is to have a speed tester as part of the ticket buying process - which would simply not allow people with slow internet to proceed to purchasing (sounds harsh, but much better they find out before than during the game) but these are very hard to build. It’s on the list though…

8. Sometimes you have to choose between modes of access

One of the things we really thought about was how we could avoid a situation where one person dominated the conversation - we have all been in Zooms like that, and it’s not fun. We had the idea of a border around everyone’s video, which would fill up and change colour according to how much they had spoke - at a glance, you’d be able to see if you had spoken more than other people. Joe built it as a design feature and we really liked it. It felt different to the regular platforms people use - and more geared to equity. But people weren’t used to noticing it - and it also needed a lot of processing power. Some people’s computers wouldn’t handle it on top of everything else the platform was doing. It might mean that those people would not be able to take part. We cut the feature: while it might help people share the airtime better, less people overall would be able to play. (We were a bit sad about this but have resolved to use the feature in a more central way in a future artwork.)

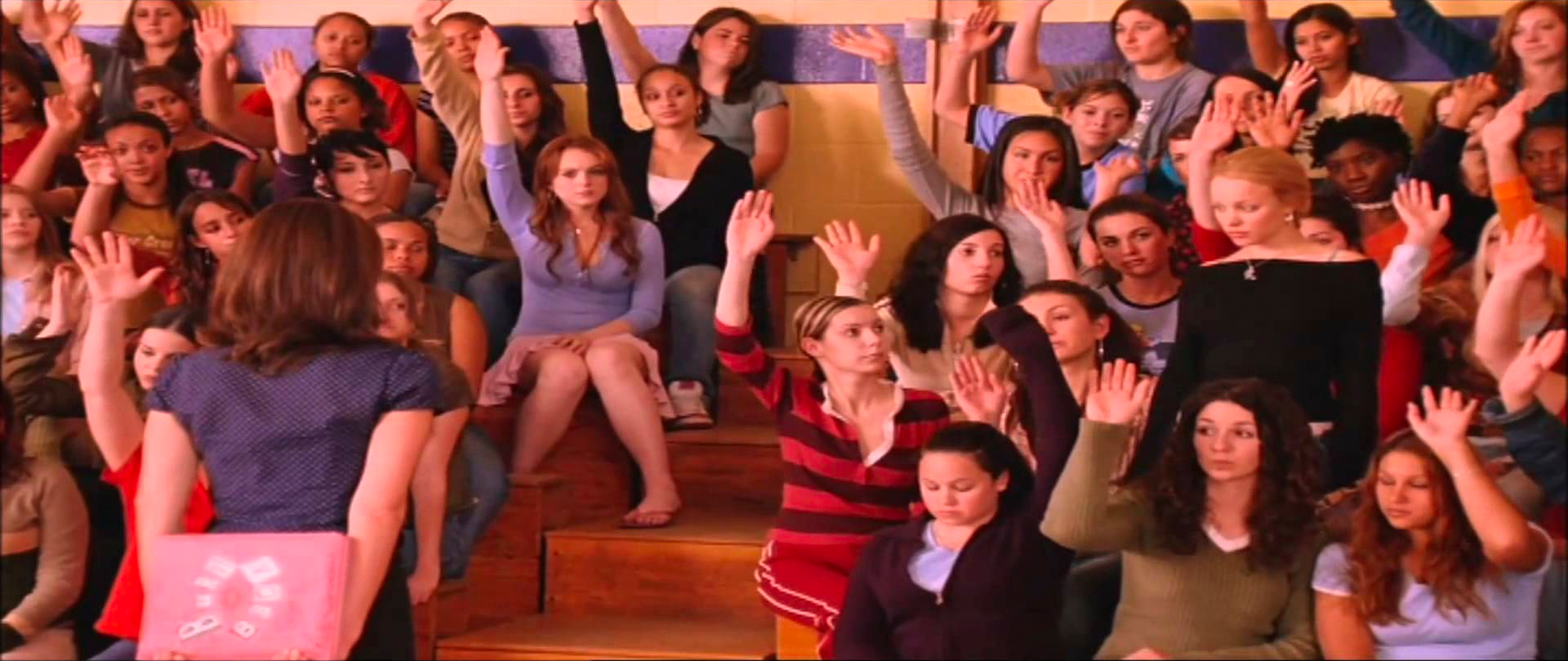

9. A bit of awkwardness is OK if it means a more equitable space

When we play The Evidence Chamber (and also The Justice Syndicate) face-to-face, we don’t have a foreman (this is term for the ‘chair’ of a jury regardless of their gender.) For the online game, we chose to. We also built a ‘hand raise’ function into the platform, to enable the foreman to see more easily who wanted to speak. Initially we felt a bit sad about adding these elements - why couldn’t the discussion flow more naturally? (One answer is because of the unavoidable latency which video calls involve.) The hand raise function initially felt awkward - but we had feedback from various people that they found the format easier than a face-to-face discussion, and participated more because of this. The additional structure created a more level environment. This made us think a lot: free-flowing discussions are easy for some people but not for others, and if we’re interested in equitable environments, maybe we should have more structure or at least declare the rules of a space? Maybe a bit of initial awkwardness is the price you pay for more people being able to participate. And that surely has to be a price worth paying?

10. There are things you can’t control/ how we learned to stop being perfectionists (temporarily) and love the mistakes (well not love them, but maybe deal with them)

We had an absolute car-crash of a dress rehearsal three days before the first real show - everything went wrong. We realised that we’d built the system as a sort of binary: it works/ it doesn’t work, with the expectation (based on previous testing) that it would work. What we needed to have done is built the system for ‘when it goes wrong’, not for ‘if it goes wrong’. So Joe spent the three days before our first show building a whole suite of tools to enable him to help people when things went wrong. This was mentally a very big shift for us to make - we’re all perfectionists and very tough on ourselves. But when people are playing on their own devices, on varied internet connections, there are so many factors you can’t control - so you can’t see things going wrong as an indication of your failure as a maker. We learnt to approach each show with the attitude ‘what will go wrong today? and how can we fix it?’ rather than ‘if something goes wrong, we are the worst artists ever and it’s game over.’ Also, we were constantly reminded throughout that audience members weren’t experiencing small blips as the total catastrophes we had seen them as. I really hope that we can find a way to keep this approach on future projects, as it’s infinitely more healthy. It also feels like a better starting point for access: not ‘this is the only way this can work’ but ‘here are the different ways and different tools we can build to make the experience work for different people’.

To be continued...